Michelle Williams’ mouth

2 July 2012

Michelle Williams’ mouth is the thing I stare at when I watch her. As an actress she can be a chameleon — I mean, Marilyn Monroe! — but in the end her mouth alone does so much to convey complicated emotions. Her mouth is what always makes her performance so distinctive.

Her mouth has gravity. Her mouth shows her disappointment, her struggles. Michelle Williams has the mouth that belies all her other beautiful attributes. Even when she enacts (very effectively) the lusciousness of Monroe, her mouth brings us back:

Whereas the real Monroe’s mouth only confirmed our mythos about her (tongue is in evidence):

Readers will know that I’ve always got my eyes open for actresses who break out of the ridiculously strict Hollywood standards when it comes to noses, mouths, body size, and other body parts so frequently adjusted by plastic surgeons. Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m certainly not saying that Michelle Williams’ mouth is unattractive or shaped oddly — far from it. Williams is a beautiful woman in many, many conventional ways.

And yet. Her full cheeks and mouth do things that render Williams’ conventional beauty so much more interesting. Her mouth almost makes me think that she doesn’t truly know how beautiful she is.

Her mouth can do things that Monroe’s refused to do: be hard, express shame or blubbering lack of control, convey a lifetime of disappointment. Whereas it seems impossible for Monroe to appear plain, Williams is at her brilliant best when that mouth draws downward and all we can see is her bald emotions, her character’s true despair.

Think about her role in Brokeback Mountain (2005) as Alma, that ordinary little thing who marries Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) knowing they’ll have a hard life together. They’re both quiet (bordering on silent, really) and dirt-poor, and once the babies start coming they’ll be poorer. That’s okay with her. It’s not like she expected anything else; she knows they’ll get old and stiff long before they ought to. But then she sees her husband kissing his friend Jack with a passion, sheer hunger and the attention she’s never gotten from him, not even once:

That bottom lip of hers is so full, so heavy. At first she’s just registering all this new information — she’s so stunned she doesn’t know how she feels. Then she knows only that she’s hurt, and the mouth drops. She’s so close to becoming ugly, and she knows she’ll be ugly if she cries.

She lets herself be ugly when they fight. She’s too angry to care anymore. She doesn’t know whether to be afraid or dare to believe that she’s the one with the power now.

That’s Williams at her most extreme, the far end of the spectrum from her Interview Face. When she sits for interviews, she disguises her expressive mouth behind a lovely and enigmatic smile. She is very good at appearing so self-possessed as to be quite evasive, as if she’s an ideal 19th-century demure heroine.

That’s Williams at her most extreme, the far end of the spectrum from her Interview Face. When she sits for interviews, she disguises her expressive mouth behind a lovely and enigmatic smile. She is very good at appearing so self-possessed as to be quite evasive, as if she’s an ideal 19th-century demure heroine.

Get it, people? She is just beautiful — a woman with spectacular cheekbones and an ability to pull off that pixie haircut. If this was all we ever saw, I’d have nothing much to say.

If I’m going to be honest, I’ll admit that what I find so great about her mouth is that it has the same natural droop as some of those older women in my family — you can see it in photos of my hardworking, stone-faced granny when she was middle-aged and saddled with an alcoholic husband. You can see it in the family photos of those other abuelas who picked cotton and had too many children and worked in canneries and stayed poor all their lives.

So maybe part of my love for that mouth is the fact that she can harness it in her acting to evoke other lives.

Williams is still too young (she is 31) and too sweet-cheeked to show the lines around the mouth that my granny had, of course. But with characters like Emily Tetherow in Meek’s Cutoff (2010) and even Cindy in Blue Valentine (2010) she shows that she can look far older than she is, far too aware of the dark side, caught in vise-like gender traps.

She has that capacity to look emotionally bruised, resigned, on the brink. She somehow encompasses both fragility and a growing hardness.

I never watched her first big role in Dawson’s Creek (1998-2003) as Jen, the city girl who grew up too fast and got sent down to live with her grandmother in a more restrained setting. From the photos I’ve seen, she appears as a far more glamorous pretty girl than I’ve seen her from her career as the darling of independent film. I prefer the latter-day Williams, discovered and used to such effect by Kelly Reichardt in Wendy and Lucy (2008) and later in Meek’s Cutoff. To find someone to inhabit the roles of these quiet women who wrangle with overwhelming problems, Reichardt needed someone with a face.

Reichardt needed someone with a face that could indicate a complicated personal history because her films don’t belabor those back stories. You need to be able to look at Wendy’s face (below) and know that, when things get complicated, she might not have the strength to face it all, partly because she’s had to face hard things before.

I’ve been marveling lately at an emotion you don’t often see on American actors’ faces, but which British actors in particular excel at: self-disgust. Nor is this emotion limited to character actors with funny faces. This emotion is most striking when it appears on the face of a strikingly attractive person. I think I first noticed it when I saw Helen Mirren in Prime Suspect (maybe even that first series, all the way back in 1991), but I’ve seen Tilda Swinton, Richard Armitage, Pierce Brosnan (of all people) and even Hugh Grant (when he’s not being a toothy douchebag) show us that they can be susceptible to the same private self-loathing as the rest of us. Mirren and Swinton are especially good at showing us that expression when they look at themselves in bathroom mirrors.

Michelle Williams hasn’t quite gotten all the way to self-disgust. Or at least I haven’t seen it yet. But we see other dark moods cross her face that aren’t quite so clear-cut. And when they do, that’s when her acting becomes most lyrical.

She’s so good at becoming that character who goes inside herself, who shuts herself off as in Blue Valentine, or who flits between her fear of uncertainty and her temptations to adultery in Take This Waltz (2011). She’s one of those actors who fosters an extraordinary relationship with her viewers (perhaps even most her female viewers, who recognize those facial expressions?) because of her seeming isolation, her impulse to make herself invisible, and the emotional gymnastics it takes for fragile people to deal with isolation.

Sometimes it just takes a small purse of the lips. To allow one’s eyes to get a bit more hooded.

Which brings me back to the odd choice of opting to portray Monroe. Why would an actress do that to herself? Why would an actress be persuaded to step into the shoes of a woman so iconic, so famed for her beauty and full-to-bursting sensuality?

For Michelle Williams to take on the role of Marilyn Monroe is not equivalent to Meryl Streep’s roles as real-life/ historic figures. Honestly: to me it sounds like a nightmare. Who among us could survive the inevitable comparisons, the naysayers who say she’s not beautiful enough to play Monroe?

Yet after thinking so extensively about Williams’ mouth and its frequent on-screen plunges downward, its gravity and its evocation of disappointment and pain, I have now determined that this must have seemed like the most extraordinary physical challenge for an actor. She has spoken extensively about gaining weight for the role and learning how to wiggle across a room with curves (whereas Williams is normally a tiny slip of a thing, like all actresses these days).

Yeah, whatever. Actors are always gaining/ losing weight and making a big noise about it, like they want to be congratulated for how hard it is. If you ask me, the real challenge was to use her mouth differently, and thereby the rest of her face. She had to loosen up her mouth, widen her eyes, adopt a new openness and insecurity to convey a wholly different breed of fragility.

In a Vogue interview, Williams said some fascinating things about stepping into this part by thinking about Monroe’s relationship to the world:

Someone once said that Marilyn spent her whole life looking for a missing person — herself. And so she cobbled together what people thought, felt, saw, and projected onto her and made a person out of it. She had no calm center inside herself that she could come home to and rest.

The challenge was to play a person so eager to please, so eager to be visible. Marilyn’s mouth always conveyed her availability; even 50 years after her death, a photo of her will make you want to run your tongue all over her beautiful open lips. What could be a better challenge for an actor like Williams — who’s prone to such a rigid private reserve — than to try to become that woman who “had no calm center inside herself”?

It’s too bad My Week With Marilyn wasn’t a better film. But that’s really beside my larger point. Someday soon I’m going to rent it again just to watch again how Williams loosens up the bottom half of her face for the role, and think again about how it contrasts with her versions of hard, disappointed, downtrodden women like Alma and Wendy.

Is there another actor out there whose mouth does so much of the heavy lifting in her acting? And in the meantime, have you gotten around to seeing her in Take This Waltz yet?

The movies I turned off, or walked out of

31 May 2012

Hot Tub Time Machine. Survived 20 minutes. So horrible I ceased to care whether it might get better. Oh, John Cusack, what happened to the Tapeheads days?

Julia. Tilda Swinton is always good in the depressive, self-loathing mode she mastered for films like We Need to Talk About Kevin, but she rarely appears as she does in Erick Zonca’s 2009 film: as a manic, beautiful alcoholic forestalling self-loathing with as many drinks as possible. But as riveting as she is, this film was unbearable to watch — the tale is so dark, and her character is on such a bleak downward spiral. Survived 35 minutes.

Julia. Tilda Swinton is always good in the depressive, self-loathing mode she mastered for films like We Need to Talk About Kevin, but she rarely appears as she does in Erick Zonca’s 2009 film: as a manic, beautiful alcoholic forestalling self-loathing with as many drinks as possible. But as riveting as she is, this film was unbearable to watch — the tale is so dark, and her character is on such a bleak downward spiral. Survived 35 minutes.

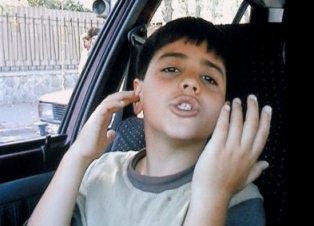

Ten. I want to like Abbas Kiarostami’s films more than I really do; I’m somewhat baffled by my annoyance. I was only able to make it through 15 minutes of this 2002 film, which apparently traces a single Iranian woman chauffeuring passengers in her car all over Tehran (with the camera positioned directly in front of the windshield, often in very long shots). The first scene, in which her son behaves badly and brattily during their ride, simply left me thinking, “Can I stand this for 5 more minutes, much less 94 more?”

Oldboy. But that’s because the Netflix version was dubbed (and badly): survived only 3 minutes. I can hardly wait to see the subtitled version. And the American remake.

The Witches of Eastwick. What’s not to like about Susan Sarandon and a story about witches? I asked myself when I turned it on. Then I discovered what not to like: Jack Nicholson in his Jack phase (ca. 1987), an impressively stupid plot, and the worst directing ever by George Miller.

Ugh. Even making a list like this puts a bad taste in my mouth. Let’s cleanse our palates with an example of how to write an Oscar-winning film, shall we? Courtesy of Cracked:

[Appreciative laughter; murmured approval; catch-phrase.]

We’ve all seen it before: the 2-yr-old is standing in the middle of the room screaming his head off. His face is red, his hands balled into comical little fists. His mother and I stare at him with a kind of exhausted paralysis. She looks at me and says flatly (and funnily), “Oh, the maternal ambivalence.” This takes place years before either of us was aware of We Need to Talk About Kevin, either book or film. Now I wish I’d seen the film with her — I can’t imagine how interesting our post-viewing debriefing could have been, how much more I could have learned from that conversation.

“Maternal ambivalence” isn’t just the right statement in a situation like when your kid has one of those histrionic meltdowns; it’s the only one to mitigate the maternal sense of failure and the simultaneous balking at calling it “failure.” If your kid behaves horribly, impossibly, inconsolably, how do you as his mother evade the sense that you ought to apologize for his awfulness, as if it’s your fault? How do you know it’s not your fault — in fact, isn’t it sort of your fault? How do you stop feeling implicated in the mini-psychodramas of a 2-yr-old – who, frankly, is probably going to act out no matter what you do? How do you help but feel that when they’re in this state, a 2-yr-old is often a kind of little animal with no reason and certainly no manners, and therefore out of your control?

“Maternal ambivalence” isn’t just the right statement in a situation like when your kid has one of those histrionic meltdowns; it’s the only one to mitigate the maternal sense of failure and the simultaneous balking at calling it “failure.” If your kid behaves horribly, impossibly, inconsolably, how do you as his mother evade the sense that you ought to apologize for his awfulness, as if it’s your fault? How do you know it’s not your fault — in fact, isn’t it sort of your fault? How do you stop feeling implicated in the mini-psychodramas of a 2-yr-old – who, frankly, is probably going to act out no matter what you do? How do you help but feel that when they’re in this state, a 2-yr-old is often a kind of little animal with no reason and certainly no manners, and therefore out of your control?

I’m hardly the first to notice that ours is a particularly hysterical culture when it comes to blaming mothers, mothers blaming themselves. I’d go so far as to say that ambivalence is a healthy response to the schizophrenic messages about what motherhood is supposed to be. With that in mind, however, let me say: We Need to Talk About Kevin is not for the faint of heart.

What you realize while watching Lynne Ramsay’s film is that we never seen representations of mothers who feel riddled by ambivalence. Dads? Sure. As bracing as Louis C. K.’s humor about being a bad parent can be, it’s popular, socially acceptable, hilarious. Mothers don’t get the same leeway. Moms are supposed to be happy, well-adjusted, delighted with their children. Pregnancy is supposed to make women glow. Motherhood, we hear all the time, is supposed to draw out women’s “natural” self-sacrificing tendencies. Good mothers, we learn, raise good children.

But then there are those dark exceptions. What about that mother who drowned all her children? Whose fault is it if your kid is a bully or a mean girl? Worst of all: when a kid kills fellow students in a school shooting rampage, who do you blame? These are some of the dark questions We Need to Talk About Kevin explores.

Eva (Tilda Swinton) wasn’t always so ambivalent. As a travel writer, she can remember some pretty transformative, ecstatic experiences; she’s not given to depression. There was that one time when she crowd surfed during that tomato festival, when she and everyone else was drenched in smashed tomatoes. You have to look carefully at first to see whether she’s hysterical or elated.

She experienced sex that night with the same giddy elation. Franklin (John C. Reilly) asked if she was sure she wanted to go without the condom — and she said yes, she was sure. For a moment there, she wants to be pregnant and knows perfectly well that their drunken, happy sex might get her there.

The actual experience of pregnancy is something else again. All those other blissful and very pregnant women stretch and happily rub their enormous bellies in the locker room of the Y after that prenatal yoga class, while Eva looks glum. She walks out of the gym amidst a stream of giddy six-yr-old ballet students and is unmoved by their pink tutued effervescence.

It doesn’t change after the birth. She doesn’t want to be this way — she just is. Even worse, he’s a colicky baby, screaming constantly. It’s even worse when she realizes that the baby quiets down the minute Franklin gets home, confirming his belief that Eva has over-reacted to the baby’s fussiness. All of this makes her feel guiltier. She’s a bad mother for not liking that baby more … but his screaming makes it all the harder. Even a jackhammer is preferable to that scream.

Look at Franklin with his son. He’s delighted. He functions as the quintessential, bright-sided American optimist. Everything’s great! And the baby responds in kind: Franklin’s presence is a balm to little Kevin. Every time his father appears, Kevin transforms into a different child.

What’s wrong with her? Is she responsible for his awful aggression? Yet she can’t help but think there’s something wrong with this child — really wrong. And when she says “something wrong,” she invokes that little kernel of anxiety that keeps you wide awake, heart pounding, at 3am with worry about what that something might be. She takes the toddler to the doctor, who gives him an unequivocal thumbs up. Whew — right?

The film ultimately makes a surprising move. Seen through Eva’s eyes, we have no doubt that Kevin is a sociopath — a brilliant, manipulative, unfeeling monster. But the film doesn’t let Eva off the hook (just as she never lets herself off). Nor is this a self-flagellating move. The film does something amazing, disturbing, revelatory: it shows that although she may not be responsible for Kevin’s psychosis, the crazy intimate antagonistic fucked-upness of their mother-son relationship is, in fact, at the very center of Kevin’s choices about acting out. Insofar as he wants, above all else, to keep her engaged with him — to provoke her out of her maternal ambivalence and malaise — she is, in fact, partly responsible, and she will never get over it.

In addition to offering us this creepy, awful realization, however, Lynne Ramsay’s film is a sustained critique of the crazy cultural contradictions we hurl at mothers all the time. Those reality shows filled with problematic children and terrible parenting — parents who cede authority to a stranger who shames them on network TV. State laws that not only permit potential employers to ask women whether they’re mothers, but which view motherhood as a “problem” for a woman doing the job (mothers are disproportionately discriminated against in hiring and promotions, and pay a “mommy penalty” in lower wages for the rest of their careers). Draconian new laws designed to criminalize “bad” mothers even when the science of such determinations is sketchy at best — these are just tips of the iceberg of schizophrenic ways that American mothers are simultaneously put on pedestals and punished. Google “mommy wars” and you’ll find infinitely more chaos.

Early on in the film Eva walks out of a job interview, feeling uncharacteristically good. As she approaches a couple of very well-heeled middle-aged women she knows, she begins to smile to greet them. One of them reaches up and smacks Eva, hard, across the face.

A man rushes up behind the stunned Eva to help, to call the cops, to do something. “No, no, no … it was my fault,” she assures him. At first this seems like the craziest, most masochistic statement you can imagine.

The thing is: she really believes it. And our culture put her there. This utterly memorable, haunting, scathing film will not let you believe those questions about nature vs. nurture, innocence vs. guilt, or good mothers vs. demon mothers are simple ones. You’ll leave this film feeling like you’ve been smacked, too.

And yet there’s something about the ending that feels … do I dare say it feels like a change in the air? Not revelation, not transformation, but something new. Please watch We Need to Talk About Kevin and tell me what you think. I for one can’t stop thinking about it.

Possible solutions to the problem of access

9 February 2012

don't mistake the Golden Globe statuette for some kind of sex toy. Or, in the state of Texas, an "educational model."

I mentioned yesterday that in my quest to see a couple of highly-respected art-house films, I’m willing to drive two hours across the state. I understand perfectly that I don’t live in an urban hub with art-house cinémas. But these films aren’t showing in Boston or in any of the other urban areas within two hours of home. Hence, I ranted about limited release, a problem I see as two-fold: I can’t see great film, and great films don’t get my money.

So here’s a solution: some version of Pay Per View. Each filmmaker eager for their film to be considered for award nominations must prove, at least one month before the nominees are chosen, that the film will be accessible to all viewers by the time of that awards show. Filmmakers can give evidence of access either by the usual means (wide release in theaters or, for films released earlier in the year, a DVD) or, for late-year releases, commitment to some form of widely-available Pay Per View — iTunes, Amazon streaming video, cable television, or an independent website (aka the Radiohead/independent music solution), or all of the above.

Thus, in order for the makers of We Need to Talk About Kevin to get its star, Tilda Swinton, nominated for Best Actress for the Golden Globes, they would have had to commit to some form of wide release by November 15, a month before the nominees are chosen. The films’ actual releases would have to occur at least one week before the awards show (December 8 in the case of the Golden Globes) with the idea that ordinary viewers would have the chance to see it beforehand.

If filmmakers cannot guarantee this release, the film will be forced to compete during the following year, when the film is available widely (presumably via DVD).

In other words, this strategy seeks to offer a middle period for award-worthy films in between very limited theater releases and wide DVD release. In that period, filmmakers can reap the benefits of wide viewership — and don’t directors really want people to see their films? — and producers can reap additional financial rewards of extra tickets sold. Streaming a film for $5.99 online is a huge attraction to me, especially if my only other option is to drive to Boston and pay $12 for a theater ticket.

There are precedents for such a move — precedents that have proved both highly profitable and great for public access. After shopping his film Red State (a fictionalized tale of a Fred Phelps-type radical Christian homophobic movement) around in the festival circuit, director Kevin Smith took his own film on the road — the 15-city Red State USA Tour. Smith’s SModcast Pictures says it spent less than $500 in advertising to support the tour, relying instead on reviews and word of mouth to encourage attendance. This decision was stunningly (and quietly) successful: it topped the per-screen average charts for three weekends, making it the highest per-screen average film of the year and the ninth-highest per-screen average film of all time, according to SModcast.

After this taking-it-to-the-streets road tour during the spring of 2011, Smith released the film in September via several online platforms, including iTunes and cable television. Now, several months later, it’s available streaming via Netflix for ordinary subscribers.

Independent musicians have used this method for years now, largely as a protest against the exploitative music industry that reserves most profits for non-artists. It’s a method made most famous by Radiohead’s In Rainbows (2007) which they released via an independent website as a digital download for which customers could set their own price. Guitarist Ed O’Brien reported of this strategy that “We sell less records, but we make more money.” Later, the band released the album in ordinary CD format at regular prices to critical and chart success.

Look, I want to see film, especially those films I’ve been hearing about for eight, nine, or ten months due to early festival screenings. I’m willing to pay to see film. But at least in terms of a few like Coriolanus and We Need to Talk About Kevin, there’s nothing I can do to see them (well, except buy a ticket to New York). These films are getting neither my viewership nor my dollars. You’d think these producers and directors would be at the forefront of experiments in change.

…in which Feminéma rants about access

8 February 2012

Perhaps you’re thinking, “where the hell is Part II of the La Jefita awards? What kind of an anonymous blogger gets me all excited about seeing a list of top films by and about women, then doesn’t tell me which one wins for Most Feminist Film?” Well, you’re not the only one who wants to rant.

I wanted to consider several 2011 films for these awards, most notably Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (Tilda Swinton, I love you) and Ralph Fiennes’ Coriolanus (so I can see Vanessa Redgrave kick the shit out of the mother stereotype), but the fact is, I can’t see them. I waited and waited, and checked showtimes everywhere within approximately 120 miles. Even if I drove all the way to Boston I couldn’t see them, because they’re not playing there, either. I don’t know what kind of moron is running those distribution companies, but if you can’t get your award-worthy film into a major American city like Boston by mid-February, you’re fucking useless.

Ahh, that feels better.

Now that I’ve ranted, and now that I’ve come to grips with the fact that I’ll have to put these films into my 2012 category (argh!), I’m prepared to re-jigger my finalists and finish this post — once I get the chance to see whether Gina Carano’s ass-kicking in Haywire is superior to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo‘s or Hanna‘s. So, friends, you can be sure to catch this post by the weekend.

Tilda Swinton in style

24 July 2011

No one else looks like her, unless you consider David Bowie a possibility. Once I showed one of her films to students and one of them pronounced her “creepy.” I’ve been entranced by her ever since seeing her shape-shifting turn as Orlando back in the 90s. Those eyes, sitting right on top of her face, not deep-set and retiring; the translucent eyebrows and lashes; the shock of copper-colored hair; the pale skin and angular frame. Now, I don’t really care about the high fashion that she looks so good in, but I do appreciate this weird and wonderful slideshow at W Magazine of photographs of her in beautiful clothes. The accompanying story is lite, but there’s a nice moment when she speaks of being entranced with her father’s military wardrobe:

No one else looks like her, unless you consider David Bowie a possibility. Once I showed one of her films to students and one of them pronounced her “creepy.” I’ve been entranced by her ever since seeing her shape-shifting turn as Orlando back in the 90s. Those eyes, sitting right on top of her face, not deep-set and retiring; the translucent eyebrows and lashes; the shock of copper-colored hair; the pale skin and angular frame. Now, I don’t really care about the high fashion that she looks so good in, but I do appreciate this weird and wonderful slideshow at W Magazine of photographs of her in beautiful clothes. The accompanying story is lite, but there’s a nice moment when she speaks of being entranced with her father’s military wardrobe:

“From childhood, I remember more about his black patent, gold livery, scarlet-striped legs, and medal ribbons than I do of my mother’s evening dresses,” she says. “I would rather be handsome, as he is, for an hour than pretty for a week.”

If you have a high pain threshold, you can watch PBS’s serial interrupter, Charlie Rose, grill Swinton on her style and lifestyle in a more substantial interview that was taped at the same time her wonderful film I Am Love (2010) was released. Rose dances around the issue of Swinton’s two lovers — her older husband and live-in younger lover — by challenging her: “But you care nothing about convention.” To which she responds: “I feel really conventional!”

Rose: “Do you?”

Swinton, somewhat awkwardly: “Yes! I’m offended that you should think I’m not conventional. It depends on what conventions you’re talking about.”

Rose: “Any … any.”

Swinton: “I had it presented to me early on that it was possible, someone like Derek Jarman…”

Rose: “Possible?”

Swinton: “To live your own life. That it is yours. I’m — surely, everybody knows this.” [She smiles enigmatically, but there’s a hint of triumph there.]

Rose, backing away and offering platitudes: “They don’t … but I think it’s one of the most important lessons you can possibly have.” Feminéma experiences gag reflex.

Let’s remember that Rose (and David Letterman of the gag-inducing US Women’s World Cup interview earlier this week) ask these questions because they are lazy, but more important believe their viewers want to see these women respond to those questions. On some level, then, they act as surrogates for an imagined middle American public. All hail to Swinton, who’s living her own life.

“Thumbsucker” (2005): see it.

28 September 2010

With a title like this, it sounds like one of those films that’s going to traffic in indie wackiness, like “Lars and the Real Girl” (2007) sounded when you first heard about it. “Lars” started out quietly wacky, so when it became wonderful and profound it snuck up on you; and while Mike Mills’ “Thumbsucker” quickly gets to a similar place, the director’s only gesture to kookiness is his (brilliant) decision to cast Keanu Reeves as a mystical orthodontist. Instead, this film opens with something disturbing — 17-year-old Justin still sucks his thumb and wants so badly to put it behind him — and slowly and gently pries open the question of identity, the crutches we use in lieu of true comfort, and the ways our needs for unequivocal love can be foiled by our unwillingness to offer it to others.

There’s something so primal, so familiar, so depressing about the way Justin (Lou Pucci) hides in a bathroom stall at school to suck his thumb. He sneaks it in at home, too, but it’s easy to get caught by his father, Mike (Vincent D’Onofrio). Neither Mike nor Justin’s mother Audrey (Tilda Swinton) know what to do about it — because they’ve got their own crutches. At the moment, Audrey’s obsessed with entering a contest to meet a cheesy TV actor, and no matter how much her sons make fun of her, she’s determined to try. “It’s just for fun!” she exclaims anytime Justin asks if there’s something up in her marriage. She means it, too — but, like Justin, there’s something she needs that she isn’t getting.

Enter, of all people, a shaggy-haired Keanu Reeves as Perry the orthodontist, who intuits Justin’s secret. He’s a breath of fresh air because he sees thumbsucking as normal, reasonable — just a problem for maintaining straight teeth. “It’s an understandable habit,” he says. “In fact, what’s strange is that people ever quit.” In a brilliantly wry short sequence (and yes, that’s the second time I’ve used “brilliant” in connection to Keanu Reeves!), he holds forth about all the small, forgotten memories that contribute to our crippled sense of self. “Some dumb babysitter holds your mouth shut so she can watch her soap operas in peace, and at forty you wonder why you can’t stay married.” He convinces a skeptical Justin to try hypnosis, which they undertake right there in the dentist’s chair, gazing at one of Perry’s hippie-dippy posters of wolves howling at the moon. It works: Justin leaves the office unable to suck his thumb anymore — but the thing is, without his thumb he has nothing, and he’s adrift. It’s no wonder that when a teacher suggests he try attention-deficit disorder medication, he leaps at the chance to solve his problems with a pill: the pill becomes his replacement thumb. And as far as Justin’s concerned, it’s awesome. Sadly, due to the beautiful strains of Elliott Smith covering Cat Stevens’ song “Trouble” — echoes of how that song infused “Harold and Maude” (1973) — we know his new confidence won’t last. (BTW: the soundtrack, mostly by the Polyphonic Spree with extra cuts by Smith, is fantastic.)

There are a lot of things to love about this film , but I’ll just focus on three: first, Lou Pucci as Justin. He’s so good (and was recognized with Best Actor honors at Sundance and the Berlin International Film Festival). He alternates between an awful kind of introversion in the earliest scenes — thumb in mouth, hair falling down over his face — to an equally awful new confidence once he becomes the relentless, successful king of his high school debate team. With his hair brushed back neatly and his deceptively innocent-looking eyes, it’s disconcerting when he takes apart other teams. “It’s my professional opinion that you’ve become a monster,” his debate coach tells him in the end. But in between Pucci offers us glimpses of true emotional openness with his big eyes and youthful hope. Which leads to my second favorite thing: Pucci’s exchanges with the inscrutable actor, Tilda Swinton, as his mother Audrey. Not only do they look like mother and son, and not only do they manage to create utterly believable scenes of typical mother-son tension; they also capture with amazing screen chemistry those few lingering moments of a more intense love for one another left over from childhood, a love that renders Pucci as soft and feminine as I’ve ever seen a male actor appear. I’d say it was quasi-sexual, though I don’t want to creep anyone out: it’s not creepy, it’s real, and such a beautiful encapsulation of how much Justin wants something from his mother that he can’t possibly articulate. I’ve never seen anything like it onscreen, and it’s great. (In fact, considering that we already know how great Tilda Swinton’s acting is, this only further underlines my first point: it great acting chops in Pucci to keep up with Swinton.)

, but I’ll just focus on three: first, Lou Pucci as Justin. He’s so good (and was recognized with Best Actor honors at Sundance and the Berlin International Film Festival). He alternates between an awful kind of introversion in the earliest scenes — thumb in mouth, hair falling down over his face — to an equally awful new confidence once he becomes the relentless, successful king of his high school debate team. With his hair brushed back neatly and his deceptively innocent-looking eyes, it’s disconcerting when he takes apart other teams. “It’s my professional opinion that you’ve become a monster,” his debate coach tells him in the end. But in between Pucci offers us glimpses of true emotional openness with his big eyes and youthful hope. Which leads to my second favorite thing: Pucci’s exchanges with the inscrutable actor, Tilda Swinton, as his mother Audrey. Not only do they look like mother and son, and not only do they manage to create utterly believable scenes of typical mother-son tension; they also capture with amazing screen chemistry those few lingering moments of a more intense love for one another left over from childhood, a love that renders Pucci as soft and feminine as I’ve ever seen a male actor appear. I’d say it was quasi-sexual, though I don’t want to creep anyone out: it’s not creepy, it’s real, and such a beautiful encapsulation of how much Justin wants something from his mother that he can’t possibly articulate. I’ve never seen anything like it onscreen, and it’s great. (In fact, considering that we already know how great Tilda Swinton’s acting is, this only further underlines my first point: it great acting chops in Pucci to keep up with Swinton.)

The third favorite thing I’ll mention about the film is that “Thumbsucker” somehow manages throughout to show all of its characters in motion — that is, Justin’s problems and his attempts  to change don’t appear against a static background, but are likened to the problems and changes of everyone else. From Perry the orthodontist to Justin’s “normal” little brother, from Audrey to the girl Justin has a crush on, each character sees things go from bad to worse and back again; everyone has a story arc. No one is normal, and everyone’s searching for the love that might bring them into equilibrium. The very last scene, in which Justin is back in that sad little orthodontist’s office while Perry sucks down a couple of cigarettes and waxes philosophical, is so perfect I wanted to cry, except it was too true and funny for that.

to change don’t appear against a static background, but are likened to the problems and changes of everyone else. From Perry the orthodontist to Justin’s “normal” little brother, from Audrey to the girl Justin has a crush on, each character sees things go from bad to worse and back again; everyone has a story arc. No one is normal, and everyone’s searching for the love that might bring them into equilibrium. The very last scene, in which Justin is back in that sad little orthodontist’s office while Perry sucks down a couple of cigarettes and waxes philosophical, is so perfect I wanted to cry, except it was too true and funny for that.

The director Mike Mills is already getting great reviews for his new film, “Beginners” (2010) with Ewan McGregor and Christopher Plummer, about a man whose father decides to come out of the closet at age 75. I can assure you I’ll be first in line when it’s released here.

I’ve plunged myself into Muriel Barbery’s wonderful novel, The Elegance of the Hedgehog, which moves back and forth between the interior monologues of two brilliant women: the autodidact Renée, who hides behind her mask as an unkempt, sullen concierge in an elegant Paris apartment building; and Paloma, the precociously intelligent 12-year-old who lives upstairs and despises the pretentions of her family, teachers, and classmates. They seem to be on a path to discover one another — but I’m at the point in the novel when I’m so enjoying just listening to them think out loud that I’m not sure I care whether the narrative goes anywhere (Paloma has a diatribe about why grammar is about accessing the beauty of language that’s so wonderful I’m thinking of plagiarizing it for use in my classes).

I’ve plunged myself into Muriel Barbery’s wonderful novel, The Elegance of the Hedgehog, which moves back and forth between the interior monologues of two brilliant women: the autodidact Renée, who hides behind her mask as an unkempt, sullen concierge in an elegant Paris apartment building; and Paloma, the precociously intelligent 12-year-old who lives upstairs and despises the pretentions of her family, teachers, and classmates. They seem to be on a path to discover one another — but I’m at the point in the novel when I’m so enjoying just listening to them think out loud that I’m not sure I care whether the narrative goes anywhere (Paloma has a diatribe about why grammar is about accessing the beauty of language that’s so wonderful I’m thinking of plagiarizing it for use in my classes).