Movies to cry to

27 June 2011

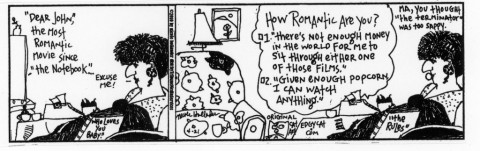

Here’s my rule: I don’t want to put any movies on this list that feel like cheap manipulators. Did I cry during The Notebook? Well, of course, and the whole time I felt as if I’d been used. In fact, I have a list of films I refuse to see because I anticipate that those tearjerkers will merely make me feel jerked around (Titanic, etc. — and despite the promises of my Dear Friend I can’t bring myself to watch Love Actually).

That said, readers of Feminéma know that I emote at the movies all the time — why, only recently I’ve mentioned having unexpected outbursts during Summer Hours, Killer of Sheep, and The Beaches of Agnès. (What can I say, but that I feel movies truly, madly, deeply?) Let me explain that this list emerges not from an eagerness to weep, but rather the firm belief that some of the best films draw tears without making you feel cheap — in fact, I’d watch these movies again this minute if I had the chance — and without making you determined never to watch them again (ahem: Breaking the Waves. Never, ever again). The tears they provoke seem to spring from something honest and human. Inspired by a comment from Tam (and borrowing shamelessly from the list she offered) this is a preliminary attempt to think about when, and how, outpourings of sentiment at the movies seem authentic as well as pleasurable.

Alan Rickman and Juliet Stevenson in Truly Madly Deeply

Weeping ritually with Departures (Okuribito, Yôjirô Takita, 2008). A beautiful film about a young man who finally gives up on his plans to be a musician and returns to his hometown to start working — mostly by accident — as someone who ritually prepares dead bodies for burial. It’s funny and surprising for many reasons, and you start to wish someone will display that much care with your body when you die.

Weeping for lost chances with 84, Charing Cross Road (David Hugh Jones, 1987). I’ve already discussed this film, which is oriented around the long, beautiful, eccentric correspondence between a New Yorker and the London bookstore clerk who supplies her with good reading material. Books, letters, and a quasi-romance between Anne Bancroft and Antony Hopkins — weeper heaven.

Weeping out of pride for your fellow humans with Harlan County, U.S.A. (Barbara Kopple, 1976). I have a whole post a-brewin’ about labor, but suffice it to say that this might be the most amazing documentary you’ll ever see — about a strike by coal miners in Kentucky who express eloquently their rights as workers in America. It brings tears to your eyes for what we’ve lost: a sense of pride in labor and the strikers’ certainty that employers are not always right. Oh, how far we’ve fallen as a nation since 1976.

Weeping for reality with The Return of Navajo Boy (Jeff Spitz & Bennie Klain, 2000). Another documentary. Sometimes my students make statements that reveal that they don’t think Indians exist anymore. This documentary about the most-photographed Navajo family in history — people typically photographed in “traditional” clothing, making blankets or some other goddamn “traditional” Indian thing — is about their real lives and the difficulties they face when most Americans refuse to believe they are anything but cardboard cutouts, much less a people whose history is always changing.

Weeping for love with Truly, Madly, Deeply (Anthony Minghella, 1990). Back to narrative film with this amazing tale of a woman missing, terribly and deeply, her dead boyfriend — when suddenly his ghost returns to her. She’s so happy to see him, except having a ghost for a boyfriend turns out to be more of a problem than it might appear at first.

Weeping for nostalgia and happiness with Up (Pixar, 2009). Criminey. Who would’ve thought, walking into a big 3-D Pixar summer release, that within 5 minutes you’d have lost weight from the weeping? Loved everything about this movie, and I’d see it again this minute, but next time I’ll have a stockpile of kleenex close by.

…and Tam also recommends The Winter Guest (Alan Rickman, 1997), which I haven’t seen yet.

Honorable mentions, for their massive tear-jerking capability primarily in the very last scenes:

- Before Sunset (Richard Linklater, 2004).

- Three films by Ang Lee: Sense and Sensibility (1995), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), and Brokeback Mountain (2005). What can I say but that that guy is crazy good at drawing big tears out of me.

- Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003).

- Toy Story 3 (Pixar, 2010).

Note that I’ve left off all the overdetermined tearjerkers: An Affair to Remember (1957) because of that cringe-making scene from Sleepless in Seattle (1993); all those dude weepers that I don’t quite get, like Good Will Hunting (1997), Field of Dreams (1989), and Brian’s Song (1971); and a couple of films like Dancer in the Dark that are just too goddamn much.

I know we’ve got a whole set of cheap stereotypes about women weeping at the movies. But the best films make us cry because we can’t help but feel with those characters. Admit it: you love it.

Movies watching movies, weeper edition

21 July 2010

What has been more maligned in the movies than the women’s weeper? Remember that scene in “Sleepless in Seattle” (1993) when Tom Hanks’ sister recalls the movie “An Affair to Remember” (1957) and gets so caught up in its high melodrama that she chokes her way through the synopsis (har har)? And yet “Sleepless in Seattle” is exactly the same kind of movie, right down to the plot device that has them meet at the top of the Empire State Building; it nevertheless feels driven to tell us, “We’re corny, but not that corny.” To hustle along to my point, I’m convinced that films are always juxtaposing themselves against other films to tell us things about plot, character, mood. But whereas they often use the weeper for cheap jokes, I’m hereby copping to my complete enjoyment of their sentimentality — and, just as important, the way they use intertextuality (sorry for the awful academese; I mean the way books and movies make reference to other books and movies). This was prompted this weekend, when I went from watching “84, Charing Cross Road” (1987) to the magnificently crisp “Brief Encounter” (1945). Movies watching movies — I love the gimmick.

Confession: I started weeping almost as soon as I started watching “84, Charing Cross Road,” based on the Helene Hanff book. This one has all the elements: trans-Atlantic letters that slowly build a kind of romantic friendship between the funny, eccentric New York writer/reader (Anne Bancroft, whom I’ll watch in anything) and the withdrawn yet soulful London bookseller (Anthony Hopkins); discussions of the love of books and good writing; lots of shots of the interiors of bookstores and people reading. You just know that they might use awful words like intertextuality too, and then laugh at themselves. It’s like porn for those of us whose G-spot is located directly on our frontal lobe.

Midway through the film the Bancroft character goes to the movies and sees “Brief Encounter” (1945), the tale of two married, middle-aged people who fall deeply in love. Nothing could be more high-British than “Brief Encounter;” Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard have accents so posh and clipped they could make any good American democrat’s skin crawl. But it’s also got high romance along the lines of “Casablanca,” to which it has been compared. The film has so many scenes of them bidding goodbye to one another on train platforms, stealing furtive kisses on romantic bridges, and looking longingly into one another’s eyes (often on train platforms!) that one wonders how the otherwise impatient and no-nonsense Bancroft character could have kept her butt in the seat. Which, in fact, is exactly why the film has her watch this weeper classic: for all her love of the highbrow (John Donne, Walter Savage Landor, Samuel Pepys) and her meeting of the minds with the shy Hopkins, Bancroft shows us that she’s just as much a sook as I am by seeing it. Not just a sook, either: by indulging herself in this sweet British romance, Bancroft indicates a tinge of longing for a man far away whom she’ll never meet.

Don’t get the wrong impression: “Brief Encounter” isn’t merely sentimental pablum, and it seeks to establish this by having Johnson (as Laura) and Howard (as Alec) watch movies, too. Most memorably they see something called “Flames of Passion” of which we only see snippets — carnal desire played out in wildest Africa sums it up neatly. In this case, the clips of “Flames of Passion” provide a clarifying backdrop for the true love and high-minded restraint of Laura and Alec, who never consummate their love. And indeed, on its release the film was hailed for its realism. If this seems absurd to you, it’s only because you’re jaded by all those send-ups of “Brief Encounter” in films like “Airplane!” — or perhaps you’re the last to rediscover the poignant elegance of 1950s melodramas by Douglas Sirk. Set aside all your snark and watch this one from the beginning, paying close attention to the actors’ faces. Howard’s sharp angles and pocked cheeks make him a realistically ordinary man, most handsome when he’s delivering his yearning, lovesick lines. (This was his first starring role; I had only seen him before in “The Third Man” as the sardonic Major Calloway.) Meanwhile, Celia Johnson’s slightly pouty mouth, enormous eyes, and batting lashes combine elegantly, sweetly, with her unabashedly wrinkled brow to confirm she was getting close to 40 when the film was made. As such Alec and Laura truly appear to be everyday people, an ordinariness that makes their passion all the more bittersweet.

Don’t get the wrong impression: “Brief Encounter” isn’t merely sentimental pablum, and it seeks to establish this by having Johnson (as Laura) and Howard (as Alec) watch movies, too. Most memorably they see something called “Flames of Passion” of which we only see snippets — carnal desire played out in wildest Africa sums it up neatly. In this case, the clips of “Flames of Passion” provide a clarifying backdrop for the true love and high-minded restraint of Laura and Alec, who never consummate their love. And indeed, on its release the film was hailed for its realism. If this seems absurd to you, it’s only because you’re jaded by all those send-ups of “Brief Encounter” in films like “Airplane!” — or perhaps you’re the last to rediscover the poignant elegance of 1950s melodramas by Douglas Sirk. Set aside all your snark and watch this one from the beginning, paying close attention to the actors’ faces. Howard’s sharp angles and pocked cheeks make him a realistically ordinary man, most handsome when he’s delivering his yearning, lovesick lines. (This was his first starring role; I had only seen him before in “The Third Man” as the sardonic Major Calloway.) Meanwhile, Celia Johnson’s slightly pouty mouth, enormous eyes, and batting lashes combine elegantly, sweetly, with her unabashedly wrinkled brow to confirm she was getting close to 40 when the film was made. As such Alec and Laura truly appear to be everyday people, an ordinariness that makes their passion all the more bittersweet.

Women’s weepers are derided for being overwrought, but what really drives them is the seeming impossibility of romance in the real world, just like the narratives that drove so many 19th-century novels. Anne Bancroft lives a continent away from Anthony Hopkins, who’s married anyway. Alec and Laura aren’t exactly unhappy with their spouses, but their new love makes their respective marriages appear tedious. The director Douglas Sirk made this even more touching, with his treatment of the class and age divides between Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in “All That Heaven Allows” (1955). Just look at this clip from “Brief Encounter” in which Laura, in the full flush of new love, fantasizes about a life with Alec (“perhaps a little younger than we are now, but just as much in love”): this vignette shows us clearly what a ridiculous dream it is, yet it allows us to indulge, even as the pieces of newspaper fly through the ratty subway under the train platform as they kiss one another, and even after she gives up her ticket and walks home:

And oh, the dialogue! What could more beautifully indicate that delicious combination of passion and restraint:

Alec, intently: I love you. I love your wide eyes, the way you smile, your shyness, and the way you laugh at my jokes.

Laura, pleading: Please don’t.

Alec, more confidently now: I love you. I love you. You love me too. It’s no use pretending it hasn’t happened because it has.

Laura: Yes it has. I don’t want to pretend anything either to you or to anyone else. But from now on, I shall have to. That’s what’s wrong. Don’t you see? That’s what spoils everything. That’s why we must stop, here and now, talking like this. We’re neither of us free to love each other. There’s too much in the way. There’s still time, if we control ourselves and behave like sensible human beings. There’s still time.

I’m telling you, go out and watch both of these movies — they’re brilliant, maudlin, beautiful things. We don’t need to secretly hate ourselves for enjoying this stuff; just use the word “intertextuality” and you’re inoculated. And besides, there’s always Sylvia to remind us that we can hate true pablum like “The Notebook.”