Possible solutions to the problem of access

9 February 2012

don't mistake the Golden Globe statuette for some kind of sex toy. Or, in the state of Texas, an "educational model."

I mentioned yesterday that in my quest to see a couple of highly-respected art-house films, I’m willing to drive two hours across the state. I understand perfectly that I don’t live in an urban hub with art-house cinémas. But these films aren’t showing in Boston or in any of the other urban areas within two hours of home. Hence, I ranted about limited release, a problem I see as two-fold: I can’t see great film, and great films don’t get my money.

So here’s a solution: some version of Pay Per View. Each filmmaker eager for their film to be considered for award nominations must prove, at least one month before the nominees are chosen, that the film will be accessible to all viewers by the time of that awards show. Filmmakers can give evidence of access either by the usual means (wide release in theaters or, for films released earlier in the year, a DVD) or, for late-year releases, commitment to some form of widely-available Pay Per View — iTunes, Amazon streaming video, cable television, or an independent website (aka the Radiohead/independent music solution), or all of the above.

Thus, in order for the makers of We Need to Talk About Kevin to get its star, Tilda Swinton, nominated for Best Actress for the Golden Globes, they would have had to commit to some form of wide release by November 15, a month before the nominees are chosen. The films’ actual releases would have to occur at least one week before the awards show (December 8 in the case of the Golden Globes) with the idea that ordinary viewers would have the chance to see it beforehand.

If filmmakers cannot guarantee this release, the film will be forced to compete during the following year, when the film is available widely (presumably via DVD).

In other words, this strategy seeks to offer a middle period for award-worthy films in between very limited theater releases and wide DVD release. In that period, filmmakers can reap the benefits of wide viewership — and don’t directors really want people to see their films? — and producers can reap additional financial rewards of extra tickets sold. Streaming a film for $5.99 online is a huge attraction to me, especially if my only other option is to drive to Boston and pay $12 for a theater ticket.

There are precedents for such a move — precedents that have proved both highly profitable and great for public access. After shopping his film Red State (a fictionalized tale of a Fred Phelps-type radical Christian homophobic movement) around in the festival circuit, director Kevin Smith took his own film on the road — the 15-city Red State USA Tour. Smith’s SModcast Pictures says it spent less than $500 in advertising to support the tour, relying instead on reviews and word of mouth to encourage attendance. This decision was stunningly (and quietly) successful: it topped the per-screen average charts for three weekends, making it the highest per-screen average film of the year and the ninth-highest per-screen average film of all time, according to SModcast.

After this taking-it-to-the-streets road tour during the spring of 2011, Smith released the film in September via several online platforms, including iTunes and cable television. Now, several months later, it’s available streaming via Netflix for ordinary subscribers.

Independent musicians have used this method for years now, largely as a protest against the exploitative music industry that reserves most profits for non-artists. It’s a method made most famous by Radiohead’s In Rainbows (2007) which they released via an independent website as a digital download for which customers could set their own price. Guitarist Ed O’Brien reported of this strategy that “We sell less records, but we make more money.” Later, the band released the album in ordinary CD format at regular prices to critical and chart success.

Look, I want to see film, especially those films I’ve been hearing about for eight, nine, or ten months due to early festival screenings. I’m willing to pay to see film. But at least in terms of a few like Coriolanus and We Need to Talk About Kevin, there’s nothing I can do to see them (well, except buy a ticket to New York). These films are getting neither my viewership nor my dollars. You’d think these producers and directors would be at the forefront of experiments in change.

…in which Feminéma rants about access

8 February 2012

Perhaps you’re thinking, “where the hell is Part II of the La Jefita awards? What kind of an anonymous blogger gets me all excited about seeing a list of top films by and about women, then doesn’t tell me which one wins for Most Feminist Film?” Well, you’re not the only one who wants to rant.

I wanted to consider several 2011 films for these awards, most notably Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (Tilda Swinton, I love you) and Ralph Fiennes’ Coriolanus (so I can see Vanessa Redgrave kick the shit out of the mother stereotype), but the fact is, I can’t see them. I waited and waited, and checked showtimes everywhere within approximately 120 miles. Even if I drove all the way to Boston I couldn’t see them, because they’re not playing there, either. I don’t know what kind of moron is running those distribution companies, but if you can’t get your award-worthy film into a major American city like Boston by mid-February, you’re fucking useless.

Ahh, that feels better.

Now that I’ve ranted, and now that I’ve come to grips with the fact that I’ll have to put these films into my 2012 category (argh!), I’m prepared to re-jigger my finalists and finish this post — once I get the chance to see whether Gina Carano’s ass-kicking in Haywire is superior to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo‘s or Hanna‘s. So, friends, you can be sure to catch this post by the weekend.

“Carlos” (2010): ur-man.

6 February 2012

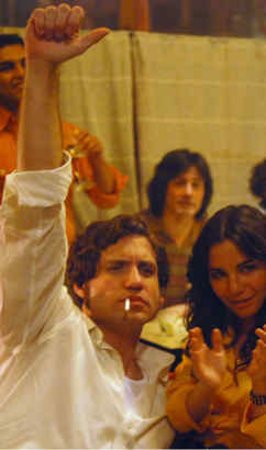

Early in Olivier Assayas’ 5½ hour epic Carlos (Carlos el chacal), we see Carlos the Jackal (Édgar Ramírez) get out of a shower in a Paris apartment and walk, dripping and naked, to a full-length mirror in another room. He wipes the water out of his eyes. He’s broad-shouldered and fit and stands with his feet apart, defiant. This shot seems at first to be a gratuitous bit of eye candy; after all, Ramírez has one of those bodies that Michelangelo might have used when creating his statue of David. But then the camera shifts and we see Carlos grab hold of his penis.

Early in Olivier Assayas’ 5½ hour epic Carlos (Carlos el chacal), we see Carlos the Jackal (Édgar Ramírez) get out of a shower in a Paris apartment and walk, dripping and naked, to a full-length mirror in another room. He wipes the water out of his eyes. He’s broad-shouldered and fit and stands with his feet apart, defiant. This shot seems at first to be a gratuitous bit of eye candy; after all, Ramírez has one of those bodies that Michelangelo might have used when creating his statue of David. But then the camera shifts and we see Carlos grab hold of his penis.

It wasn’t my first cue that Assayas is trying to tell us something, and that it has something to do with Carlos’ manliness, his sexuality, and the sexual charge of 1970s militant liberationist activism (or, in 2010s parlance, terrorism). Assayas is not being, ahem, subtle. We may not feel comfortable with Carlos, but the director keeps suggesting we recognize him as a kind of ur-man, a man with primal instincts, superior intelligence for survival, and big sexual appetites.

Before I continue, let me say that Carlos is a film I did not believe could be made just yet, and which makes me wonder if we’ve reached a true post-post-9/11 moment. I say this because of the film’s subject matter as much as the way it makes a terrorist the central anti-hero of the story. It’s a terrific and compelling piece of filmmaking, all the more so because you find yourself uncomfortably rooting for him.

Before I continue, let me say that Carlos is a film I did not believe could be made just yet, and which makes me wonder if we’ve reached a true post-post-9/11 moment. I say this because of the film’s subject matter as much as the way it makes a terrorist the central anti-hero of the story. It’s a terrific and compelling piece of filmmaking, all the more so because you find yourself uncomfortably rooting for him.

Carlos is a prequel to the rise of al-Qaeda: Carlos and his legions of revolutionaries are working for the Palestinian cause in the wake of Israel’s Six-Day War, and they are always 10 steps ahead of law enforcement. (Carlos and his associates are Marxists, but it’s easy to see how his tactics if not his ideals were embraced by militant jihadists. “For me the only struggle that matters is the oppressed against the imperialist.” By the end he has converted, he says, to Islam.)

Assayas’ film makes us in turns awed and appalled, admiring and turned on — and all by a man whose propensity for violent chaos now seem abhorrent. In a 1970s world of lax security, Carlos and his partners walk into airports with missile launchers, hijack planes, kidnap the entire roster of an OPEC meeting. It’s truly stunning and shocking if you, like me, were too young to remember/know about any of this. (I think I finally understand why people loved Reagan and Rudy Guiliani for making the world seem safer and Disney-clean.)

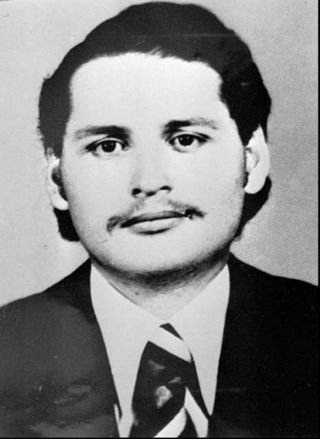

I mentioned a couple of days ago that Édgar Ramírez is a looker, whereas the real Carlos (née Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, so named by his Marxist Venezuelan parents after Lenin) was not. In real life, Carlos looks like a slightly dweeby kind of guy. It’s hard to imagine he stands above average height, although it’s hard to know how tall he really is because photos of him seem to be either mug shots from his younger days in the 70s or photos of him sitting in court as a 60-something man. All of these photos, I might add, make him look like someone who might have a good (and perhaps slightly wicked) sense of humor. He’s prone to corpulence and a smirk that enhances the wicked look.

I mentioned a couple of days ago that Édgar Ramírez is a looker, whereas the real Carlos (née Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, so named by his Marxist Venezuelan parents after Lenin) was not. In real life, Carlos looks like a slightly dweeby kind of guy. It’s hard to imagine he stands above average height, although it’s hard to know how tall he really is because photos of him seem to be either mug shots from his younger days in the 70s or photos of him sitting in court as a 60-something man. All of these photos, I might add, make him look like someone who might have a good (and perhaps slightly wicked) sense of humor. He’s prone to corpulence and a smirk that enhances the wicked look.

In contrast, Ramírez is broad-shouldered, barrel-chested, and Hollywood gorgeous; yet it’s not just his looks, nor that he’s utterly riveting to watch, and apparently incapable of smirking or displaying a sense of humor, that draws my attention. It’s that Assayas has created a different Carlos — a hunky, single-minded, and somewhat humorless sex king who seems taller than everyone around him. You’d never guess that actor Ramírez is 5’10”, because the way it’s filmed you’d think he was 6’3”. He’s riveting, charismatic, and unflinching, and he always seems to be towering over at the other characters with his steely gaze. It’s hard to imagine that Carlos might ever walk into a room without everyone turning to watch him.

In contrast, Ramírez is broad-shouldered, barrel-chested, and Hollywood gorgeous; yet it’s not just his looks, nor that he’s utterly riveting to watch, and apparently incapable of smirking or displaying a sense of humor, that draws my attention. It’s that Assayas has created a different Carlos — a hunky, single-minded, and somewhat humorless sex king who seems taller than everyone around him. You’d never guess that actor Ramírez is 5’10”, because the way it’s filmed you’d think he was 6’3”. He’s riveting, charismatic, and unflinching, and he always seems to be towering over at the other characters with his steely gaze. It’s hard to imagine that Carlos might ever walk into a room without everyone turning to watch him.

The filmmaker continually draws our attention to Carlos’ sexuality and his casual misogyny. Assayas does so explicitly by getting Carlos out of his clothes and into women’s beds; and implicitly, by having him decisively dominate other men — whether he’s managing a crew of revolutionaries, talking with hostages, or negotiating with politicians or military leaders.

Women are convenient. They hide his weapons for him, agree with his positions. When he inevitably cheats on one of them or leaves her for someone else, she gets violently jealous, not understanding that “I am a man. I have my needs.” All he needs to do is move his hand between a woman’s legs, and she begins to writhe like a porn star.

When he meets revolutionary Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstätten), for example, they speak briefly about the possibility of her working for him as a forger. But she wants more:

Magdalena: I would like to make myself useful in a more active manner.

Carlos: I don’t trust women. They never know how to keep their heads.

Magdalena: I see you’re not afraid of clichés.

Carlos: No, I’m not. Because there’s always some truth in them, especially concerning German feminists.

Magdalena: Well. I confess: I am a German feminist. Disappointed?

Carlos: Yes. Very much.

Magdalena, leaning back in a chair and casually exposing her breast: And what do you know about German feminists?

Carlos: Well, I know they are sexually liberated; that they sleep with men and women alike; and if you give them weapons you never know what can happen.

Magdalena: Hm. Are you thinking of Nada? She’s just been sentenced to fourteen years in prison.

Carlos: But she won’t stay there long. I usually don’t abandon my friends.

Magdalena: So I’m only worthy of your prejudiced ideas.

Carlos: Am I wrong?

Magdalena, shaking her head: I left my little daughter behind. I walked out on my petit bourgeois lifestyle. I did it to devote myself to the anti-imperialist struggle. [Walks across the room and retrieves a gun from her luggage.] And I’ve also learned to use weapons. [She cocks the gun.] Correctly.

Next thing you know, his hand is between her legs and she’s moaning as if it’s Debbie Does Damascus. If this weren’t such a serious film, that scene would make you think it was Pay Per View — and even worse that dialogue that discusses clichés would so quickly become one. Near the end, when he develops a testicular condition, the only rational reaction is, well, he had that coming, didn’t he?

If self-proclaimed feminists throw themselves at him, then golly, he must be a tiger in bed! Now, I’m as happy as the next person to watch Édgar Ramírez get it on with the ladies; but even given his lusciousness I still rolled my eyes at the film’s claim that he was masterful in the sack. Why? Because considering how much of the film was a fictionalization of Carlos’ life and relationships, director Assayas is deploying Ramírez ‘s hotness as shorthand to create a complex portrait of the real-life revolutionary.

What I’m hoping is that when you hear it framed in those terms, you’ll appreciate how cheap a move that is for such an otherwise high-quality film.

One of the scenes that might be true — insofar as the woman was an informer to the police — takes place in the film’s 3rd part, when Carlos flirts with a couple of prostitutes in a bar and winds up getting a blow job from one of them in the bathroom. When she moves away from him to use the sink, we see an out-of-focus Carlos standing behind her, staring at her with menace; that steely, square-jawed impassivity that makes him so dominant now appears truly psychopathic. It’s a great shot and not a cliché in the least, unlike the (invented?) scenes with Magdalena. Carlos comes up from behind the woman and whacks her, all of which she later describes to the intelligence unit. Now that seems like the kind of man Carlos might truly be: a man who wants women to service him, and who hates them enough to hurt them afterward.

My complaints about these clichéd plot points are for Assayas, not Ramírez, who’s terrific in this role. He portrays Carlos as a clear-eyed, unsentimental, unblinking radical who understands the power of violence and the violence of power. (And a cunning linguist: he moves in and out of the languages of Spanish, French, German, English, and Arabic with ease — and apparently it was only Arabic he needed to learn for the role.) But honestly, directors: figure out how to develop complex male figures without just having them get women into bed. Those clichés damage men as well as women — and more important, they make for lazy, and mockable, filmmaking. Figure out instead how to show us that a dweeby, corpulent guy can be charming and oversexed and complex without demanding that we gaze up at him, turned on by his lusty stereotypical Hollywood-style masculinity.

Assayas risks glamorizing Carlos in other ways — by backing up his exploits with a terrific soundtrack with such acts as early New Order, Wire, the Dead Boys and the Feelies. But that’s not my real complaint. It’s just that the director opts for exactly the kind of masculinity and cheap misogyny that would have appeared in a 1930s gangster movie. Sigh.

Placeholder for “Carlos” (2010)

2 February 2012

I’ve been working my way through the 5 ½ hour made-for-TV epic (clearly in France, they have a very different kind of “made-for-TV”) by Olivier Assayas, starring the terrific Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez as the 1970s international terrorist Carlos the Jackal. I’ve got a lot to say. But because I’m racing around today, and because my thoughts need to cohere, I’m going to point out that the real Carlos (left) is a very different-looking man.

I’ve been working my way through the 5 ½ hour made-for-TV epic (clearly in France, they have a very different kind of “made-for-TV”) by Olivier Assayas, starring the terrific Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez as the 1970s international terrorist Carlos the Jackal. I’ve got a lot to say. But because I’m racing around today, and because my thoughts need to cohere, I’m going to point out that the real Carlos (left) is a very different-looking man.

What?!? A filmmaker found a better-looking guy to play the part?? Stop the presses!

Yeah, yeah, I know. Remember at the end of Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), when they all show up to watch the Hollywood version of Pee Wee’s story — and it turns out they got James Brolin and Morgan Fairchild to play Pee Wee and Dottie, and Pee Wee himself was reduced to a hotel clerk?

But keep it in mind anyway. There are some strange things going on in Assayas’s Carlos, and they have to do with sex & gender, and I feel like saying them.

I also feel like noting that the 70s were whack. Between Carlos and the amazing documentary Man on Wire (2008) about Philippe Petit’s 1974 high-wire walk between the two World Trade Center buildings, I feel as if I have no understanding whatsoever of a decade during which I was actually alive.

“Where the Sidewalk Ends” (1950)

31 January 2012

When I think of old Hollywood glamour and mystery, I think Gene Tierney. Like Hedy Lamarr and Merle Oberon, she had one of those faces that just seemed to convey so much — more, maybe, than existed in real life. She has an almost Asian face, with those unusually slanted pale eyes; but then there’s her oddly out-of-place mouth, which looks perfect closed but seems pinched when she speaks. Being entranced by her surely dates from my seeing the classic film noir Laura (1944) at a very impressionable age.

In Laura, the other characters talk about her mostly in flashback for an excruciatingly long period of time because she’s presumed dead — and they speak about her with such reverence that the gritty, laconic police detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) starts to fall in love with her in a clumsy way, gazing at her portrait. Maybe it’s easy to idealize a dead woman; no one has any doubts about why McPherson falls so hard. As a kid watching it for the first time I had no idea that she would appear, like a vision, midway through the film, not dead at all, and slightly harder in real life than the idealized version would have had her. It’s a terrific plot twist — and the only problem I ever had with that brilliant film was that I was never sure why Laura fell for him, too.

So imagine my delight to discover Where the Sidewalk Ends, also starring Andrews and Tierney, also directed by the great Otto Preminger. I can’t emphasize enough what a great film this is, and such a great follow-up to Laura. Andrews’ character is even named Mark again, which gives Tierney the chance to pronounce it Mahwk in that same low, refined way. Andrews is a complicated, crooked anti-hero, much more fleshed out and darker than in the earlier film; his mouth is set in an even more unforgiving, hard line, especially in all those bitter close-ups. It’s as if he’s still that other Mark, except more brutal. And Tierney almost seems to be Laura again except a sad six years and an unhappy marriage later. She’s just as beautiful, but a bit haunted and still attracted to the wrong men.

The earlier film Laura haunts Where the Sidewalk Ends just the way the portrait/fantasy of Laura haunted Mark McPherson. But in the latter, their tentative romance plays out against the gritty city streets of New York, filmed beautifully on location, and in an ordinary little café, owned by an older woman Mark helped out of a jam that one time. The two of them banter/bicker back & forth at one another in a practiced way, which delights Tierney — who wouldn’t be charmed by a man whose biggest fan likes to joust with him while serving him bowls of soup?

See this film — it’s streaming on Netflix. Better yet, give yourself a two-night double feature of both films, in order. This is film noir at its best, and tell me whether it makes you fall for Tierney’s mystery as well.

Oscar “snubs”: Get. A. Grip.

30 January 2012

Richard Brody, the film blogger for the New Yorker, has decided that Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar biopic was “snubbed” by the Oscars because the film pleased neither left-leaning critics, who felt the film was a “whitewash” of Hoover’s career, nor right-leaning critics, who hate the gay stuff.

Let’s get a grip.

Now, lots of times I like films that no one else seems to like — or perhaps I like them more than the majority did. Who can account for taste, right? No one likes to hold forth about how a film was misunderstood more than I do.

Now, lots of times I like films that no one else seems to like — or perhaps I like them more than the majority did. Who can account for taste, right? No one likes to hold forth about how a film was misunderstood more than I do.

But let’s say I was holding forth, and I discovered this film had only a 44% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, as J. Edgar does. Well, maybe I’d have to admit that it might just not be very good.

Now, of course, these could be the misunderstood critics Brody’s talking about. Let’s read some reviews — and what do we find? Not a left-right battle over the memory of a shadowy historical figure, but complaints that it’s just not a very good film. Rotten Tomatoes sums it up as, “Leonardo DiCaprio gives a predictably powerhouse performance, but J. Edgar stumbles in all other departments with cheesy makeup, poor lighting, confusing narrative, and humdrum storytelling.” Hmmm…doesn’t look like a political battle at all, Brody!

Then there’s the question of “snubs.” There a lot of people complaining about which films never appeared on the Oscars’ radar — lord knows I love to complain! — but these are usually independent or foreign films that get overlooked all the time. I wouldn’t use the word “snub” because it’s more like, “Who ever heard of Pariah?”

You know what film got ignored? Lee Chang-dong’s Poetry, Feminéma’s La Jefita Film of the Year. Poetry gets a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. That’s a lot, lot better than 44%, from a lot of critics — and it’s not because it has simple politics.

Pariah gets 95%. Higher Ground and We Need to Talk About Kevin each get 81%. Neither of these panders to audience expectations, either. These films were criminally overlooked. But “snubbed”? That term implies entitlement.

Is it a snub because J. Edgar stars Leonardo DiCaprio, who’s supposed to receive nominations for everything he does?

Is it a snub because it was directed by Clint Eastwood, one of our “national treasures” and is guaranteed nominations?

Is it a snub because Oscar voters are supposed to like biopics all the time, because they are Important?

Here’s a radical suggestion: let’s pretend, at least in Blogland, that no film is guaranteed nominations just because of who’s behind it. Or because “I liked it, and I’m associated with the New Yorker, so therefore….”

You’ll see right away that this is not all BBC and Jane Austen. Once I started constructing this list, I realized that there’s no material difference between The Godfather, Parts I and II and The Forsyte Saga. They’re usually literary adaptations (which range from cynical to gritty to romantic to eminently silly). They almost always tell intense, character-driven tales of families or communities to throw the reader into a moment in the past — not just for history geeks or people with weird corset fetishes. Period drama ultimately addresses issues of love and power, adventures and domestic lives, self-understanding and self-delusion, and the institutions or cultural expectations of the past that condition people’s lives. Class boundaries, sexism, political institutions, and (less often) race — seeing those things at work in the past helps illuminate their work in our own time.

Most of all, it makes no sense that period dramas are so strongly associated with “women’s” viewing. Okay, it does make sense: PBS is dribbling Downton Abbey to us every Sunday, and my female Facebook friends twitter delightedly afterward. But that’s just because all those dudes refuse to admit that Deadwood is a costume drama, too. This is a working draft, so please tell me what I’ve missed — or argue with me. I love arguments and recommendations.

- American Graffiti (1973), which isn’t a literary adaptation but was probably the first film that wove together pop songs with the leisurely yearning of high school kids into something that feels literary. Who knew George Lucas could write dialogue like this? An amazing document about one night in the early 60s that Roger Ebert calls “not only a great movie but a brilliant work of historical fiction; no sociological treatise could duplicate the movie’s success in remembering exactly how it was to be alive at that cultural instant.”

- Cold Comfort Farm (1995),

which functions for me as true comfort on a regular basis. This supremely silly film, based on the Stella Gibbons novel and directed by John Schlesinger, tells of a young society girl (Kate Beckinsale) in the 1920s who arrives at her cousins’ miserably awful farm and sets to work tidying things up. I can’t even speak about the total wonderfulness of how she solves the problem of her oversexed cousin Seth (Rufus Sewell); suffice it to say that this film only gets better on frequent re-viewings. (Right, Nan F.?)

which functions for me as true comfort on a regular basis. This supremely silly film, based on the Stella Gibbons novel and directed by John Schlesinger, tells of a young society girl (Kate Beckinsale) in the 1920s who arrives at her cousins’ miserably awful farm and sets to work tidying things up. I can’t even speak about the total wonderfulness of how she solves the problem of her oversexed cousin Seth (Rufus Sewell); suffice it to say that this film only gets better on frequent re-viewings. (Right, Nan F.?) - Days of Heaven (1973), the lyrical film by Terrence Malick about migrant farm workers in the 1910s and narrated by the froggy-voiced, New York-accented, cynical and tiny teenager Linda Manz. Beautiful and elegant, and one of my favorite films ever — and a lesson about how a simple, familiar, even clichéd story can be enough to shape a film and still permit viewers to be surprised. (The scene with the locusts rests right up there as a great horror scene in film history, if you ask me.)

- Deadwood (2004-06), the great HBO series about Deadwood, South Dakota in its very earliest days of existence — a place with no law, only raw power. Fantastic: and David Milch’s Shakespearean dialogue somehow renders that world ever more weird and awful. Excessively dude-heavy, yes; but hey, by all accounts that was accurate for the American West in the 1860s. And let’s not forget about Trixie.

- The Forsyte Saga (2002-03), the Granada/ITV series based on the John Galsworthy novel which I wrote about with love here. Those turn-of-the-century clothes! The miseries of marriage! The lustful glances while in the ballroom! The many, many episodes!

- The Godfather Parts I and II (1972, 1974). I still think Al Pacino’s work in these films is just extraordinary, considering what a newbie he was to film acting; and the street scenes with Robert De Niro from turn-of-the-century New York in Part II! spectacular! Directed by Francis Ford Coppola and based on the Mario Puzo novel, of course, with political intrigues and family in-fighting that matches anything the 19th-century novel could possibly produce.

- Jane Eyre (2011), again, a film I’ve raved about numerous times. I’ve got piles of reasons to believe this is the best version ever, so don’t even try to fight it. ‘Nuff said.

- L.A. Confidential (1997), a film by Curtis Hanson I’ve only given glancing attention to considering how much I love it. At some point I’ve got to fix this. It won’t pass the Bechdel Test, but by all accounts the sprawling James Ellroy novel about postwar Los Angeles was far more offending in that regard; and despite all that, Kim Basinger’s terrific role as the elusive Veronica Lake lookalike is always the first person I think of when looking back on it. She lashes into Edmund Exley (Guy Pearce) mercilessly, and he wants her all the more. Of course.

- Little Dorrit (2008), which saved me from one of the worst semesters of my life — shortly to be followed by two more terrible semesters. This was a magic tonic at just the right time. Charles Dickens at his twisting, turning best; and screenwriter Andrew Davies doing what he does best in taking a long novel and transforming it for a joint BBC/PBS production. Oodles of episodes, all of which are awesome.

- Lust, Caution (2007), which I only saw this month. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen such a sensual, dangerous, beautifully-acted period film. And that Tang Wei! I’m still marveling over her performance. Ang Lee directed this WWII resistance thriller, based on a novel by Eileen Chang.

- Mad Men (2007-present). It’s been a while since Season 4, which I loved; they tell me the long-awaited fifth season is coming back to AMC this March. Oh Peggy, oh Joan, oh Betty, and little Sally Draper…whither goes the women in Season 5? I’m not sure there’s a modern director amongst us who cares so much for both the historical minutiae (a woman’s watch, the design of a clock on the wall) and the feeling of the early- to mid-60s as Matthew Weiner.

- Marie Antoinette (2006),

surely the most controversial choice on this list. Director Sofia Coppola creates a mood film about a young woman plopped into a lonely, miserable world of luxury and excess. The back of the film throbs with the quasi-dark, quasi-pop rhythms of 80s music — such an unexpected pairing, and one that really just worked. Kirsten Dunst’s characteristic openness of face, together with her slight wickedness, made her the perfect star.

surely the most controversial choice on this list. Director Sofia Coppola creates a mood film about a young woman plopped into a lonely, miserable world of luxury and excess. The back of the film throbs with the quasi-dark, quasi-pop rhythms of 80s music — such an unexpected pairing, and one that really just worked. Kirsten Dunst’s characteristic openness of face, together with her slight wickedness, made her the perfect star. - Middlemarch (1994).

Can you believe how many of these films & series I’ve already written about? Juliet Aubrey, Patrick Malahide, Rufus Sewell et als. just bring it with this adaptation of George Eliot’s sprawling (and best) novel. Marriage never looked so foolish, except until Galsworthy wrote The Forsyte Saga. It’s yet another BBC production and yet another terrific screenplay by Andrew Davies.

Can you believe how many of these films & series I’ve already written about? Juliet Aubrey, Patrick Malahide, Rufus Sewell et als. just bring it with this adaptation of George Eliot’s sprawling (and best) novel. Marriage never looked so foolish, except until Galsworthy wrote The Forsyte Saga. It’s yet another BBC production and yet another terrific screenplay by Andrew Davies. - My Brilliant Career (1979), the film that initated me into costume drama love, and which gave me a lasting affection for Australians. Judy Davis, with those freckles and that unmanageable hair, was such a model for me as a kid that I think of her as one of my favorite actresses. Directed by the great Gillian Armstrong and based on the novel by Miles Franklin about the early 20th century outback, this still stands up — and it makes me cry a little to think that Davis has gotten such a relatively small amount of attention in the US over the years.

- North and South (2004). The piece I wrote on this brilliant BBC series is very much for the already-initiated; at some point soon I’m going to write about how many times I’ve shown this little-known series to my friends practically as a form of evangelism. “The industrial revolution has never been so sexy,” I was told when I first watched it. You’ll never forget the scenes of the 1850s cotton mill and the workers’ tenements; and your romantic feelings about trains will forever been confirmed.

- Our Mutual Friend (1998), which I absorbed in an unholy moment of costume-drama overload while on an overseas research trip.

You’ll never look at actor Stephen Mackintosh again without a little pang of longing for his plain, unadorned face and quiet pining. Another crazy mishmash of Dickensian characters, creatively named and weirdly motivated by the BBC by screenwriter Sandy Welch for our viewing pleasure.

You’ll never look at actor Stephen Mackintosh again without a little pang of longing for his plain, unadorned face and quiet pining. Another crazy mishmash of Dickensian characters, creatively named and weirdly motivated by the BBC by screenwriter Sandy Welch for our viewing pleasure. - The Painted Veil (2006). Now, the writer Somerset Maugham usually only had one trick up his sleeve; he loved poetic justice with only the slightest twist of agony. Maugham fans won’t get a lot of surprises in this John Curran film, but this adaptation set in 1930s China is just beautifully rendered, and features spectacular images from the mountain region of Guanxi Province. It also features terrific performances by Naomi Watts, Liev Shreiber (slurp!), and especially Edward Norton, who’s just stunningly good.

- The Piano

(1993), written and directed by the superlative Jane Campion about a mute woman (Holly Hunter) and her small daughter (Anna Paquin) arriving at the home of her new husband, a lonely 1850s New Zealand frontiersman (Harvey Keitel) who has essentially purchased them from the woman’s father. As with Lust, Caution you’d be surprised how sexy sex in past decades can be. And the music!

(1993), written and directed by the superlative Jane Campion about a mute woman (Holly Hunter) and her small daughter (Anna Paquin) arriving at the home of her new husband, a lonely 1850s New Zealand frontiersman (Harvey Keitel) who has essentially purchased them from the woman’s father. As with Lust, Caution you’d be surprised how sexy sex in past decades can be. And the music! - Pride and Prejudice (1995). Is it a cliché to include this? Or would it be wrong to snub the costume drama to end all costume drama? Considering this series logged in at a full 6 hours, it’s impressive I’ve watched it as many times as I have. Jennifer Ehle, Colin Firth, and a cracklingly faithful script by Andrew Davies — now this is what one needs on a grim winter weekend if one is saddles with the sniffles.

- The Remains of the Day (1993). I still think the Kazuo Ishiguro novel is one of his best, almost as breathtaking as An Artist of the Floating World (why hasn’t that great novel been made into a film, by the way?). This adaptation by Ismail Merchant and James Ivory gets the social stultification of prewar Britain and the class system absolutely. Antony Hopkins, Emma Thompson, and that Ruth Prawer Jhabvala script!

- A Room With a View (1985), which I include for sentimental reasons — because I saw it at that precise moment in my teens when I was utterly and completely swept away by the late 19th century romance. In retrospect, even though that final makeout scene in the Florentine window still gets my engines runnin’, I’m more impressed by the whole Merchant/Ivory/Jhabvala production of the E. M. Forster novel — its humor, the dialogue, the amazing cast. Maggie Smith and Daniel Day Lewis alone are enough to steal the show.

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1996). This novel runs a pretty close second to Jane Eyre in my list of favorite Brontë Sisters Power Novels (FYI: Villette comes next) due to the absolute fury Anne Brontë directed at the institution of marriage. And this BBC series, featuring Tara Fitzgerald, Toby Stephens, and the darkest of all dark villains Rupert Graves, is gorgeous and stark. I haven’t seen much of Fitzgerald lately, but this series makes you love her outspoken sharpness.

- Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011), Tomas Alfredson’s terrific condensation of a labyrinthine John Le Carré novel into a 2-hour film. Whereas the earlier version — a terrific 7-part miniseries featuring the incomparable Alec Guinness as Smiley — was made shortly after the book’s publication, Alfredson’s version reads as a grim period drama of the 1970s. I dare you to imagine a more bleak set of institutional interiors than those inhabited by The Circus.

- True Grit (2010), the Coen Brothers’ very funny, wordy retelling of the Charles Portis novel that has the most pleasurable dialogue of any film in my recent imagination. The rapid-fire legalities that 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) fires during the film’s earliest scenes; the banter between Ross, Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges), and La Boeuf (Matt Damon) as they sit around campfires or leisurely make their way across hardscrabble landscapes — now, that’s a 19th century I like imagining.

- A Very Long Engagement (2004), Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s sole historical film and one that combines his penchant for great gee-whiz stuff and physical humor with a full-hearted romanticism. Maybe not the most accurate portrayal of immediate period after WWI, but what a terrific world to fall into for a couple of hours.

A few final notes: I’ve never seen a few classics, including I, Claudius; Brideshead Revisited; Upstairs/Downstairs; Maurice; and The Duchess of Duke Street. (They’re on my queue, I promise!)

I included Pride and Prejudice rather than Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility and I’m still not certain I’m comfortable without it. But secretly, I think I liked Lee’s Lust, Caution a little bit better.

There are no samurai films here, despite the fact that I’m on record for loving them. Why not? I’m not sure. Maybe it’s because I have no grasp whatsoever of Japanese history, and the films I know and love seem to see history less as something to recapture than to exploit. I’m certain I’m wrong about that — tell me why.

I reluctantly left off 2009’s A Single Man because it’s just not as good a film as I would have liked, no matter how good Colin Firth was, and no matter how gorgeous those early ’60s Los Angeles homes.

That said, you need to tell me: what do you say?

“The Artist” (2011): how to fall in love

28 January 2012

The scene: an old 1920s theater with Art Deco designs and original (i.e., uncomfortable) chairs. Most of the audience is over age 65. They show us some previews and then the curtains on either side of the screen scoot in a bit, narrowing the view, because The Artist was filmed in the aspect ratio of 1.37:1, just like old movies were. That very shape of that screen — virtually unseen in my lifetime except to watch old movies on TVs that used to be shaped like this (still are, for us old-school types) — makes me feel warm and happy, as if someone has handed me a down duvet to curl up in.

I have trouble understanding the rumblings from anti-Artist critics. This is a post about why.

I giggled from the film’s very earliest silly moments. I found myself so attached to Uggie, the dog, that I considered getting a dog. And I cried: the big melodramatic moment came and I was truly moved, with big affectionate tears running down my face. What a relief: after watching the trailer approximately 30 times, I had fretted the full-length film couldn’t live up.

I giggled from the film’s very earliest silly moments. I found myself so attached to Uggie, the dog, that I considered getting a dog. And I cried: the big melodramatic moment came and I was truly moved, with big affectionate tears running down my face. What a relief: after watching the trailer approximately 30 times, I had fretted the full-length film couldn’t live up.

That’s the thing, you see: director Michel Hazanavicius has created a primer for audiences unfamiliar with classic film, and what he teaches is how to fall in love with cinéma. For the rest of us who already love those early films, it’s a love letter. A very different love letter than the one Martin Scorcese created with Hugo, and one that’s more affecting.

For me, the key to the film is that it understands the central, simple brilliance of early film: The Artist asks only that you to fall in love with the two main characters, and especially to enjoy their falling in love. Peppy Miller (Bejo) lands a role in the new big film starring George Valentin (Dujardin), and she winds up as an extra in a silly scene in which he must dance with her briefly as he makes his way across the room. But as we see in a series of takes, he keeps flirting with her, joking, each time requiring a new take — and each time it’s a little harder for him to get back into character to start the scene again for a clean take.

In short: director Michel Hazanavicius isn’t pedantically telling us about the history of cinema. (I found Hugo delightful but a bit pedantic.) Rather, he’s given us a way to connect emotionally with cinema that most of us aren’t familiar with, and which gives unexpectedly pure delight. Some filmgoing pleasures are old ones, with a few sight gags tossed in.

Hazanavicius’s interviews have been great to read in part because it’s clear he feels his love for old film so passionately. Asked by a reporter for Chicago’s The Score Card about the differences between this and his earlier OSS 117 film, he explains:

The most important change was the absence of irony. There’s no irony in this movie. Quick into writing this movie, I watched a hundred silent movies. The ones who aged the best were melodramas and romances. And even the issue with Charlie Chaplin is that people think he is a comic, but his films are melodramas. Pure melodramas, nineteenth century dramas.

There’s no winking at you. The film isn’t saying, I know that you know that I know this is all stupid, even if it’s sweet. This is a 21st-century version of a classic silent film.

The closest it comes to a wink is when the film plays with sound. There are a couple of early scenes, designed to get us to laugh, that introduce us to the experience of watching a film with no sound. The subject of sound becomes a prominent theme — whether films will use it, whether audiences prefer it, whether Valentin might be right about resisting the big transition to talking film. Sometimes it’s used initially to prompt laughter, like at the beginning of a dream sequence.

But that sequence quickly turns to eerie nightmare, showing us what Valentin really fears: irrelevance. And somehow that scene is resonant beyond the gag at the center of it — making us viewers feel the threat of sound, and the safety of silence, at least in Valentin’s eyes.

The best melodramas always have dark elements, characteristics that ring true. One of these is Valentin’s hubris. I don’t want to oversell the film’s story — it’s determined to remain light melodrama — but nevertheless I found it surprisingly touching to see how Valentin wrestles with his pride and growing public insignificance.

What made that story so appealing, I think, was the paired tale of Peppy Miller’s rise to stardom and how she experiences her own expanding success as being related to Valentin’s fall — that is, the fall of a man she loves without disguise. Her need for him is something that you almost feel corporeally from those scenes of her very long arms. Again, I don’t want to oversell this story; maybe my appreciation for it is predicated on hearing so many critics accuse Hazanavicius of creating a mere pastiche. Suffice it to say that I believe some critics have underestimated the story’s resonance.

Of course I can see that director Hazanavicius creates a number of scenes by quoting from all manner of earlier movies — Astaire and Rogers, James Whale’s Frankenstein, The Thin Man, even Citizen Kane. Yet again to fly to his defense, I see those quotes as being done out of an abiding love of film and a consciousness of the way film is always quoting from itself. (Remember The Ides of March and Moneyball? Constant references to other films!) If you watch movies purely out of a desire to see something new, you’re depriving yourself of some of the joys of cinema.

So, what’s the difference between “quoting from” other films and “creating a pastiche”? Again, I’d say it has to do with whether the film ultimately seems self-conscious, ironic, winking at us. Maybe some viewers see The Artist as an amalgam of other things, but that wasn’t my experience, and nor was it Hazanavicius’s intention, according to his interviews.

Most of all, I believe Hazanavicius chose silent film, specifically, for a good reason: to teach us something we’ve collectively forgotten. He wants to show what film could do when we had to use our eyes so searchingly. Within a few days of seeing the film — and reading a few more reviewers who called this a gimmick or a form of pandering — I became more convinced that the director may not be a pedagogue, but he certainly wants us to learn something in the course of watching this film.

To wit: in my theater, you could hear the viewers gradually starting to laugh more, to intuit the internal logic of a silent film. Even though most of them were 65+years old, it’s hard to imagine any of them had ever seen a silent film on the screen while they were growing up. They started vocalizing non-words more — with silent film, you don’t need an audience to be silent — so you could hear people uttering things like, “ahh,” “oh!” and “wow” (especially when Jean Dujardin tap-danced). That low-level, unobjectionable audience murmuring enhanced the experience of watching, contributed to the communal pleasure. But it’s something we had to learn in the course of watching it.

I have the teensiest of complaints about ‘s The Artist — that some scenes felt like a mishmash of 1920s, 30s, and 40s influences, and that however charming she is, Bérénice Bejo seemed too tall and twiggy for the era — but my full range of emotions during the course of the film shows the limitations of my small criticisms. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I just burbled with the unmitigated pleasure of watching film, like when I saw the pitch-perfect grizzled face of Malcolm McDowell in a bit part (below). Oh, hang on, I experienced the same when I re-watched Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in the frothy Top Hat (1935) on New Year’s Eve.

And oh, Jean Dujardin! He can look beefy during his Douglas Fairbanks scenes, “who, me?” disarming during his William Powell scenes, and fantastically light on his feet during his Gene Kelly scenes; egotistic early on, depressive later. And when he gets himself into a love scene with Bejo … well, he has a gravity, and a genuine sense of surprise and feeling, that makes us feel as if we’re falling in love, too. (In a way, we are.)

It’s strange that I loved the film this much and yet it took so long to express it here — I saw it nearly a month ago. It seems so horribly stereotypical that I, as an academic, would formulate a pile of tedious words to analyze something that’s like a visual soufflé. But there you have it — academics are bound to try to deflate the beautifully, improbably fluffy in order to understand how it works.

Should it win Best Picture and Best Actor at the Oscars? I think its only serious competition is Hugo and, as I’ve indicated, there’s no question for me that The Artist is better. I’ll also have to see Demián Bichir in A Better Life before I weigh in on Question #2. It’s my opinion that the Oscars put up a weak list this year (where is Poetry? where is Higher Ground? why are Moneyball and The Help up there?), and that given those lists, I’m rooting for The Artist. What can I say? Michel Hazanavicius shows us how to fall in love with cinema, and in love with a love story — and I went there with him. I hope you do, too.

Academia as gothic horror

25 January 2012

And they say professors are ineffective, boring types who spend all their time thinking about the esoteric. Clearly they haven’t been reading the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Usually academic novels emphasize satire. No one who has ever attended a faculty meeting doubts there’s plenty to mock. Also, satire is easier; it’s a form of humor that does not ultimately throw one into a state of existential angst or lead one to ask oneself, “Should I just quit this stupid job?” One tends to try to view one’s own work with the same sardonic grimace and soldier on.

But let’s face it — the worst aspects of academic are not grimly amusing but horrific. (James Hynes understood this with his utterly memorable collection of gothic-horror novellas, Publish and Perish: Three Tales of Tenure and Terror. Hynes, how did you also manage to make me laugh during these tales?)

But let’s face it — the worst aspects of academic are not grimly amusing but horrific. (James Hynes understood this with his utterly memorable collection of gothic-horror novellas, Publish and Perish: Three Tales of Tenure and Terror. Hynes, how did you also manage to make me laugh during these tales?)

In this week’s Chronicle we learn of the operatic drama taking place at San Francisco’s California Institute of Integral Studies, where two anthropology professors — a husband-and-wife team — have been fired after having worked at the Institute for 25 and 14 years, respectively. The school charges them with having “breached student confidence, falsified grades, misapplied funds, and otherwise engaged in unprofessional conduct, generally to ensure the loyalty and obedience of those they taught and advised.” Moreover, the school says it was

“shocked at the climate of fear and intimidation” Ms. Chatterji had fostered, and it found “deeply disturbing” Mr. Shapiro’s complicity in creating such a climate, “centered around a cultlike idealization” of his wife. It said his “unwavering and uncritical support” for his wife “gave little hope for reform or remediation.”

Where’s a screenwriter when you need one? “Cultlike idealization”? “Climate of fear and intimidation”? This is Hollywood gold! (Sorry, the Chronicle article is password-protected, but you can read more here.)

So here’s a couple of recommendations to screenwriters:

You have to capture the subject position of grad students accurately to convey the horror of this situation. All grad students are under the thumb of, indebted to, and subject to the whims of faculty advisors. Some advisors are good and ethical people; many are not. Many view grad students as clinging, unsatisfactory servants who need to just figure out how to be brilliant on their own. Some of them use grad students as chauffeurs, grading machines, or dartboards. Chatterji and Shapiro were accused of using grades to demand servile loyalty from grad students. But I also know of cases in which advisors demanded blow jobs from their female grad students or complained bitterly that a student had married someone the advisor disapproved of. Actually, I know other stories too, and I’m sure you do as well.

You have to capture the often nonsensical world of academic celebrity — those rare figures who achieve national or international acclaim for their work and command fawning respect from students and fellow faculty alike. In a strange world driven by intellectual insecurity and indefinable, vague notions of “importance,” no one among us can ascertain which individuals or books or articles are truly Important. Rather, it’s determined by ubiquity: if the crowd seems to be running in that direction, they must have a good reason. “Well, if Professor X’s book keeps getting used in grad classes and cited by scholars, it must be Important.” Thomas Kuhn, anyone? Structure of Scientific Revolutions? It often makes no sense why one academic becomes a celebrity and another does not.

And finally: You have to capture the ways academics are unable to keep boundaries between their personal lives and their work lives. This article makes reference to Chatterji and Shapiro gossiping about their grad students’ personal lives widely even after promising total confidentiality. For many academics, gossip is a way to traffic in power — but it’s also fun for its grisly combing over of personal details. Conferences are horrible places because of the gossip.

Looking forward to the film — aren’t you? And in case anyone needs a consultant for writing this script, I’m available at didion [at] ymail [dot] com!