Declaring inde-fem-dence

14 April 2012

Now this is a good idea. Public declarations of “I need feminism because…” — by smart young people, including Duke students, and during an election year. Sing it, brothers and sisters.

I’ve never quite understood why Keira Knightley is an A-list star, nor why she gets such good roles (like Atonement, Pride & Prejudice, and Never Let Me Go) – until I saw her in David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method (2011). It always seemed to me she was being cast against type. Whereas those earlier films insisted she was a quintessential English rose, as Lizzie Bennet in P&P she appeared to me more likely to bite one of her co-stars than to to impress anyone with her fine eyes.

What Cronenberg gets (and I didn’t, till now) is that Knightley’s angular, toothy, twitchy affect shouldn’t be suppressed but mined instead.

Now that I’ve finally seen A Dangerous Method, I can’t imagine another actor taking on the role of the hysteric Sabina Spielrein to such effect. Jewish, Russian, fiercely intelligent and tortured by her inner demons, Sabina is the perfect dark mirror sister of Jung’s blonde and blue-eyed wife (Sarah Gadon), who always appears placid, wide-eyed and proper, and sometimes apologizes for errors such as giving birth to a daughter rather than a son. Now that’s a rose of a girl.

Maybe she seems exaggerated, but Jung’s wife embodies the self-control and physical containment of their elite class as well as their whiteness. No wonder Jung (Michael Fassbender) is so thrown by Sabina. For all her physical contortions, Sabina is also open to change, open to the darkest of insights. She opens up her mind and her memories to him with stunning willingness, revealing black thoughts associated with dark sexual urges. The more she ceases repressing those memories and associations, the more she reconciles them and begins to heal — and begins to use her quicksilver smarts in a way that shows her full embrace of the “talking cure”. No wonder she captivates Jung’s imagination, which is only the beginning of his growing disloyalty to his wife.

Knightley’s impossible skinniness only enhances her performance here. Whereas in most other films her body gets presented to us as yet another ridiculous size-00 slap in the face to the rest of us fat pigs (and don’t you forget it, Ashley Judd), in A Dangerous Method her body exemplifies a lifetime of self-punishing neurosis. There’s nothing more improbable than seeing her heavy dark eyebrows and her olive skin — and hearing about her sexual arousal via humiliation — all the while bound up in those cruel corsets and lacy, white, high-necked dresses that on any other woman would be persuasive signifiers of her chastity.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that what I found most impressive about Knightley’s performance was the way she showed how the later, “healed” Spielrein — the one who no longer screams and juts out her chin — was a recognizable incarnation of the earlier hysteric. Her clenched and slightly hunched shoulders, her black looks, her tight mouth. She’s a whirlwind of intellect and energy, and the performance is brilliant. As the excellent JB writes over at The Fantom Country, “Even in relatively calmer moments, she seems trapped inside a state of ceaseless panic, caught, gasping for air, in the dragnet of some trawler that never sleeps.”

This is especially important for the contrast between her corporeal presence versus that of Jung and Freud, who exert an absurd degree of self-control and containment, like disembodied brains. When she kisses Jung for the first time, his weak response is to note, “It’s generally thought that the man should be the one to take the initiative.” When someone refers to the “darker differences” between the two, we know those differences are both racial and sexual — and that Spielrein is the dark one, the one whose vagina has needs and rages, and smells like a real woman’s vagina (thanks to Kartina Richardson’s terrific piece, “Keira Knightley’s Vagina”). It makes me wish that Knightley rather than Natalie Portman had appeared as the lead in Black Swan — again, a statement I never thought I’d make.

Spielrein and Jung’s other patient, Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), both profess to a startling optimism about analysis: “Our job is to make our patients capable of freedom,” Gross pronounces, a sentiment Spielrein shares but cannot realize. Her own ecstasy peaks as Jung gives her erotic spankings; clearly, humiliation still retains its primary charge. The film doesn’t explore the gendered nature of hysteria, which brought so many women low during those decades a hundred years ago, but it does highlight how one’s freedom was limited by other cultural boundaries — most notably race. Spielrein looks genuinely crushed when her new interlocutor, Freud, pushes her down with the observation, “We’re Jews, Miss Spielrein — and Jews we will always be.”

We don’t very often call it hysteria anymore, but we still see manifestations of inexplicable corporeal neurosis in girls and women that defy explanation, as in the strangely infectious case in upstate New York this year. How amazing it would be to find a filmmaker to address the subject. I’ve always thought that someone could take the 1690s Salem witch hysteria as a case study, Arthur Miller-style, to try to explore some of the contributing factors behind such mass outbursts of tics, twitches, and personal misery. And I’d love to have Knightley involved again, honestly.

People love to talk about the synergy between Cronenberg and his frequent male lead, Mortensen, as being one of the great director-actor combinations of the last decade. But now that I’ve seen what Cronenberg got out of Knightley, I want him to unearth new roles for her instead so we can see more of what she can really do once she lets go of the English rose routine. I totally get it now: Knightley can act. And I’m genuinely looking forward to more of it.

Her name is Tarantella (Tandra Quinn). Are not her charms sufficient to persuade you to watch this film?

Her name is Tarantella (Tandra Quinn). Are not her charms sufficient to persuade you to watch this film?

How about the fact that it’s set in a remote, lonely part of Mexico, where Dr. Araña has a crazy science lab hidden deep in a cave where he experiments with spiders? “Hey, Araña means spider in Spanish!” proclaims one of the unlucky souls sucked into the scientist’s orbit. (So there’s also the crackling dialogue.)

The Wasp Woman was the first feature in my Mini-Marathon of Cult Horror Movies about Female Monsters — and it shares something in common with Mesa of Lost Women: the theme that science is dangerous. But whereas poor Janice Starlin believed the wasp venom would make her look younger with no side effects (oh, woman’s vanity and foolishness!) Dr. Araña has less scientifically justifiable aims.

He just likes to see what happens when you mess around in a crazy lab with humans and spiders.

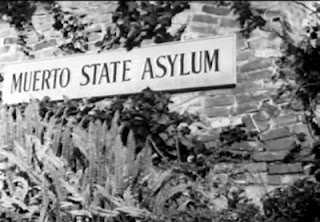

Sure, Mesa of Lost Women suffers from some writing, editing, acting, and directing foibles — remember, I’m not conducting this marathon because I expect these films to surprise me with their high quality. But if you look past the interminable, nonsensical voiceovers and your own guffaws at the hairpin plot twists, we get back to Tarantella. Because out here in the Muerto Desert (yes, it’s that subtle: muerto) some very strange gender dynamics are at work, just like we’d hoped when we started this marathon.

Tarantella’s body looks like it’s been cross-pollinated with hydraulics, but in fact it’s the implantation of a spider pituitary gland that makes her so … arachnoid. She doesn’t speak; her eyes are always bugging out; her hands are often clenched in fingernail-y claws. One can only admire how her strapless dress stays up (can we chalk that up to the spider blood in her veins?). Cue the Bitch Semiotic!

Oh, she’s a bitch all right. These 1950s sci-fi horror films are full of references to all those female bugs that eat their mates. Tarantella will gaze hungrily at whatever man comes into view — all of whom turn into jelly with a single glance at her.

Let’s remember that movies like Mesa of Lost Women had the fundamental role in American culture of the 1950s of providing just enough titillation and spookiness to allow teenagers to keep up the heat while they make out in cars parked in drive-in theaters. This film succeeds.

Scariest of all, Tarantella knows how to dance. In a bizarre sequence of events so convoluted it’s not worth explaining, Tarantella arrives at a little bar where the mariachi music begins and she shakes her badunkadunk. It’s utterly bizarre and hypnotic. “She’s fascinating!” says the riveted Jan as he watches her. “As a dancer, of course,” he adds as a quick cover-up to his blonde fiancée.

Scariest of all, Tarantella knows how to dance. In a bizarre sequence of events so convoluted it’s not worth explaining, Tarantella arrives at a little bar where the mariachi music begins and she shakes her badunkadunk. It’s utterly bizarre and hypnotic. “She’s fascinating!” says the riveted Jan as he watches her. “As a dancer, of course,” he adds as a quick cover-up to his blonde fiancée.

Oh, this video is so deliciously whack.

There’s a terrific blogger over at the brilliantly titled blog And You Call Yourself a Scientist! who’s written the most extensive, knowledgeable assessment of this film that I almost feel overwhelmed. (Almost.) This blogger makes a particularly astute point about how boring these movies often are. Having deferred most knowledge to that blogger, let’s talk about the Bitch Semiotic and the role of the sexpot monster in films like this.

Point 1: Tarantella is guilty of any number of vague crimes of the sort that women commit against men, but she’s really only a serf who follows Dr. Araña’s evil directives. She dances, but she never speaks. She hypnotizes in order to lure men into her web and uses that killer body of hers to ensure men’s doom. Can you say “bitch on wheels”? All of this makes the motivations of Janice Starlin from The Wasp Woman seem unbelievably sensitive and complex in contrast.

What could be more revealing of men’s ideas about women in the 1950s than a vivid, bitchy death dancer who’s a slave to her male master?

Point 2: I’m wondering how often these Cult Female Monsters engage in what we might call the Sexy Dance of Death — and whether any of the others could possibly touch the weirdness of Tarantella’s. Is the Bitch Semiotic of this genre of cult horror films especially reliant on elaborating the monster’s bitchiness via dance? Stay tuned for more on this subject! This film provides not just the Sexy Dance, but also the patented Cat Fight® so essential to portrayals of women.

And finally, Point 3: to fully explore the subject of the Bitch Semiotic in Cult Horror Films with Female Monsters, I’m starting to see that we need to break them down into categories. In the vein of the abovementioned blog And You Call Yourself a Scientist!, I’m thinking about categories something like this:

- Science gone wrong (The Wasp Woman, Mesa of Lost Women, etc.)

- Religion gone wrong (the appalling Cobra Woman, for example)

- Bitten! (monster bites woman and transforms her into a monster, revealing all manner of fascinating infection fears)

- Bitchez from outer space (I can hardly wait!)

- Family curse (à la Cat People)

These categories will, I think, clarify even more the universe of the mid-century male psyche about women and gender. And I’m fairly convinced that Bitchez from Outer Space needs to come next, aren’t you?

“Girls’ brains aren’t good with science and math.”

11 April 2012

Many, many thanks to Jen for sending me a link to this graphic she’s designing to combat myths about women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Click on it to get a larger image and decipher the footnotes. I’m curious, are any of my readers in STEM? And does the logic of this graph — that women are discouraged to proceed into those fields — ring true? Because I’m getting sick of these arguments that take culture out of the equation. (Just yesterday, news broke that Gov. Scott Walker of Wisconsin repealed the state’s equal pay law, a move defended by a crony who pronounces that “money is more important” to men than women.)

Thanks again, Jen and the team at EngineeringDegree.net — and I hope the rest of you have more to say about these hoary stereotypes. How much do you want to bet that women who are good at STEM regularly face charges that they are a) bitchez, or b) too talented to be women at all, à la Brittney Griner?

Respects amongst the plots

6 April 2012

If you google the cemetery where she’s buried, you find that she’s lying beside a wide range of semi-famous crime figures. Many have nicknames that render their portraits as fearsome and quixotic, like Tough Tony and Frankie Shots. On the other hand, one was a horse trainer nicknamed Sunny. The name Capone is mentioned more than once. There’s also a smattering of turn-of-the-century boxers and policemen of Irish descent, Diamond Jim Brady (a man known for his gluttony, among other things), some minor state legislators, and that character actor who played the loyal bodyguard Luca Brasi in The Godfather.

Considering her feelings about respectability, it’s a good thing she didn’t know ahead of time about the life histories of most of her bedfellows here. But if she had, she might have cracked a joke: at least they were Catholics. Actually, I always assumed statements like that were jokes — but what do I know? Maybe she meant them seriously.

Considering her feelings about respectability, it’s a good thing she didn’t know ahead of time about the life histories of most of her bedfellows here. But if she had, she might have cracked a joke: at least they were Catholics. Actually, I always assumed statements like that were jokes — but what do I know? Maybe she meant them seriously.

Although I’ve tramped through a large number of historic cemeteries lately, it’s been done out of my curiosity about ancient methods of burial rather than to pay my respects to anyone in particular. I mean, one can’t come to Boston without a few of the oldest burying grounds or the glamorous 19th-century Mount Auburn Cemetery out in Cambridge with all its Brahmins, exotic trees, and garden design. My family, in contrast, is not the cemetery-oriented type; our own dearly departed are buried all over the country, seldom more than one or two per cemetery. History bats ordinary people all around the country, willy-nilly.

One might go so far as to say that my family’s story of itinerancy is representative of the whole. Our nation is now so mobile, so transient, that we can no longer harbor the fantasy that one’s whole family might be gathered together at last, lined up in a row under a stone that ties all of you together by a family name or two.

There’s also the question of changing ideas about burials and remembrance. I’m fairly certain I don’t need a plot in a cemetery, my name on a stone, even if my bedfellows have names like Frankie Shots. I sort of like the idea of a makeshift service, à la Walter and The Dude scattering Donny’s ashes all over themselves near the end of The Big Lebowski.

In the middle of the cemetery, somewhat inexplicably, a sign reads PLOTS. Perhaps it was intended as a road sign in the vein of those no-duh signs you sometimes see announcing THICKLY SETTLED or WATCH OUT FOR CHILDREN. Still, one can’t help but read it for the double meaning of the word plots, the meaning that ties it to storytelling.

My grandmother didn’t have a nickname as glamorous as Tough Tony, but aren’t all of us just a mess of plots? She in particular was full of stories and family gossip. These cemeteries are full of them. My sister and I stand in front of her stone, thinking about those stories she told that never quite cohered into one as memorable as Diamond Jim’s — but there you have it. Paying our respects out there in the plots.

“Margaret” (2011): the poem that breaks

5 April 2012

It’s ironic that, during this film of all films, I’d be sitting in front of loud talkers. It was two 60-something women, women who looked immaculately put together. I asked them to please stop talking; they didn’t. I tried turning around and glaring at them; I shushed them. Other people shushed them. One of them seemed to get louder, as if to spite us. Who does this? Who feels self-righteous about talking in a theater after being shushed?

It’s ironic that, during this film of all films, I’d be sitting in front of loud talkers. It was two 60-something women, women who looked immaculately put together. I asked them to please stop talking; they didn’t. I tried turning around and glaring at them; I shushed them. Other people shushed them. One of them seemed to get louder, as if to spite us. Who does this? Who feels self-righteous about talking in a theater after being shushed?

Talking in a theater may be one of the smallest of rudenesses, but it’s ironic because Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret treats such a tangle of related topics I almost wondered whether the women had been planted behind me as a form of performance art. This film is a poem about guilt and self-righteousness, childishness and alienation, bad behavior and misplaced blame in a chaotic universe. Its subject matter is so apt for our world, encompassing everything from spats between mothers and teenage daughters to the very largest questions about 9/11 or Israel/Palestine, that I feel gutted upon leaving it. Lisa (Anna Paquin) is a teenage asshole in the vein of Rutgers student Dharun Ravi, whose lawyers recently tried to argue in court that he wasn’t homophobic when he set up a webcam to catch his gay roommate inflagrante with another man; rather, they argued, Ravi was only guilty of being a typical college-age asshole. That defense didn’t save Ravi from being declared guilty of bias intimidation. In Lisa’s case, being a typical teenage asshole means she’s accustomed to such mundane thoughtlessness that she has no idea what to do with the consequences of her own actions when they are shown, uncontrovertibly, to make her guilty of the most serious crimes.

Lisa (Anna Paquin) is a teenage asshole in the vein of Rutgers student Dharun Ravi, whose lawyers recently tried to argue in court that he wasn’t homophobic when he set up a webcam to catch his gay roommate inflagrante with another man; rather, they argued, Ravi was only guilty of being a typical college-age asshole. That defense didn’t save Ravi from being declared guilty of bias intimidation. In Lisa’s case, being a typical teenage asshole means she’s accustomed to such mundane thoughtlessness that she has no idea what to do with the consequences of her own actions when they are shown, uncontrovertibly, to make her guilty of the most serious crimes.

It won’t spoil anything to tell you that very early on in the film, she witnesses — and is partly responsible for — the gruesome death of a woman crossing an ordinary street in New York. Like any typical teen, Lisa tries to suppress the event, returning to the usual business of an overprivileged private-school kid: lazy performances on tests and in her debate class, boys, snapping at her mother. But gradually that business takes on an edge it didn’t have before. She jerks around one boy by messing with a different one; her sharp-tongued takedowns of her mother have a bitterness she can’t control; her debates in class turn vicious. Lisa becomes the human manifestation of Dr. Doolittle’s pushmi pullyu, simultaneously grasping for and pushing back at everyone around her. It’s so frantic, this pushing and pulling, that it starts to look almost sociopathic.

It won’t spoil anything to tell you that very early on in the film, she witnesses — and is partly responsible for — the gruesome death of a woman crossing an ordinary street in New York. Like any typical teen, Lisa tries to suppress the event, returning to the usual business of an overprivileged private-school kid: lazy performances on tests and in her debate class, boys, snapping at her mother. But gradually that business takes on an edge it didn’t have before. She jerks around one boy by messing with a different one; her sharp-tongued takedowns of her mother have a bitterness she can’t control; her debates in class turn vicious. Lisa becomes the human manifestation of Dr. Doolittle’s pushmi pullyu, simultaneously grasping for and pushing back at everyone around her. It’s so frantic, this pushing and pulling, that it starts to look almost sociopathic.

That neurotic quality of her own behavior is not lost on her. So she belatedly decides to mourn the woman who died in her arms, and those feelings ultimately morph into something more complicated — feelings Lisa clearly cannot handle. Does she want some kind of retribution? Is it enough to drag other people along with her on these emotional highs and lows? Will she feel better if she just wins a few arguments with her mother or in her debate class?

That neurotic quality of her own behavior is not lost on her. So she belatedly decides to mourn the woman who died in her arms, and those feelings ultimately morph into something more complicated — feelings Lisa clearly cannot handle. Does she want some kind of retribution? Is it enough to drag other people along with her on these emotional highs and lows? Will she feel better if she just wins a few arguments with her mother or in her debate class?

You can’t help but fret when she forms an attachment to the dead woman’s best friend (Jeannie Berlin) — a beautiful woman about the age of Lisa’s mother with an appealing, deliberate pattern of speech that contrasts sharply to Lisa’s patter. Is it the woman’s grief that draws the teenager, or is it the illusion of calmness in her carefully-chosen sentences?

One of her teachers asks her early on whether she’s ever found herself suddenly fascinated by something she’d never shown an interest in before. “No,” she says, like the asshole she is, like the teenager who feels bound and determined to be contrary, independent. Yet something eats away at her edges. When her English teacher (Matthew Broderick) reads the Gerard Manly Hopkins poem, “Spring and Fall/ To a young child,” we see a glimpse of something — is it interest, or is it recognition?

One of her teachers asks her early on whether she’s ever found herself suddenly fascinated by something she’d never shown an interest in before. “No,” she says, like the asshole she is, like the teenager who feels bound and determined to be contrary, independent. Yet something eats away at her edges. When her English teacher (Matthew Broderick) reads the Gerard Manly Hopkins poem, “Spring and Fall/ To a young child,” we see a glimpse of something — is it interest, or is it recognition?

- Margaret, are you grieving

- Over Goldengrove unleaving?

- Leaves, like the things of man, you

- With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

- Ah! as the heart grows older

- It will come to such sights colder

- By and by, nor spare a sigh

- Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie.

- And yet you will weep and know why.

- Now no matter, child, the name:

- Sorrow’s springs are the same.

- Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

- What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

- It is the blight man was born for,

- It is Margaret you mourn for.

Does she hear that poem, its warning words about mortality, about self-recognition, about the cruel side of such understanding? When her teacher asks her to comment, she snaps back at him that she has nothing to say.

Between Anna Paquin’s talent and Kenneth Lonergan’s perfect dialogue — this man has reproduced teenager talk like no one I’ve ever heard — you find yourself spending 150 minutes with a person who is, unlike Hopkins’ Margaret, neither truly a child nor very likeable, yet still somehow riveting to watch. She’s so reckless with that force of will, so angry. No one escapes her lash, least of all herself. You can’t watch this film without decrying the fact that Paquin has settled in for wallowing in all that campy True Blood TV nonsense (and let’s not forget the blonde dye job and the nasty tan), because in this role she shows a crazy genius for being way too smart and mean and unhinged, so much so that she comes close to despising herself.

Perhaps the most famous thing about this film (and the reason for its stingy limited release to only a few theaters in the U.S.) is the battle between director Lonergan and the distributors at Fox Searchlight. After completing the film in 2006, Lonergan embarked on a years-long battle with the distributor over its length. Whereas the director’s cut was nearly 3 hours long, the distributor demanded that it be cut by at least 30 minutes. Only after the intervention of Martin Scorcese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who together produced a 150-minute version that the director signed off on, did the film finally get released late last year — and then only in a tiny number of theaters. A grassroots movement of critics quickly grew up to keep the film in theaters and earn it a wider release (to limited success).

Even if I hadn’t known this back story, I would have noticed the film’s choppiness. I opened by calling this film a poem about guilt, and I mean it seriously — but it is a broken, choppy poem whose breaks and abrupt transitions feel increasingly messy as the film moves along. Anyone who knows and loves Lonergan’s perfectYou Can Count On Me(2000) knows that he is capable of laser-like poetic focus, unity, and subtlety, perhaps more than any other director you can think of. This is a broken poem, one that forces you to see its jumps and awkwardnesses.

But how is it possible that the film’s editorial choppiness nevertheless has a poetry of its own? It somehow nails down the film’s overall themes, and underlines them. Someday I want to see Lonergan’s own director’s cut; I can only hope he finds a way to release it on DVD when the time comes. But no matter how beautifully that version might flow from scene to scene, I won’t forget the way this version told me something else about the emotional pinball engendered by traumatic events, and the way a person might intermittently compartmentalize her own responses to the world around her.

But how is it possible that the film’s editorial choppiness nevertheless has a poetry of its own? It somehow nails down the film’s overall themes, and underlines them. Someday I want to see Lonergan’s own director’s cut; I can only hope he finds a way to release it on DVD when the time comes. But no matter how beautifully that version might flow from scene to scene, I won’t forget the way this version told me something else about the emotional pinball engendered by traumatic events, and the way a person might intermittently compartmentalize her own responses to the world around her.

My greatest fear is that Lonergan’s fight with Fox will embitter him to the screenwriting and directing he’s so extraordinarily good at. And if there’s anything I learned from watching Margaret, it’s that we need Kenneth Lonergan to help us through our ugly world. The film’s conclusion (resolution?) is so real, so simple, that it cut through the loud, rude chatter of those women behind me, such that I couldn’t muster much more anger toward them. Life is too short; as the heart grows older it will come to such sights colder.