Movies watching movies, weeper edition

21 July 2010

What has been more maligned in the movies than the women’s weeper? Remember that scene in “Sleepless in Seattle” (1993) when Tom Hanks’ sister recalls the movie “An Affair to Remember” (1957) and gets so caught up in its high melodrama that she chokes her way through the synopsis (har har)? And yet “Sleepless in Seattle” is exactly the same kind of movie, right down to the plot device that has them meet at the top of the Empire State Building; it nevertheless feels driven to tell us, “We’re corny, but not that corny.” To hustle along to my point, I’m convinced that films are always juxtaposing themselves against other films to tell us things about plot, character, mood. But whereas they often use the weeper for cheap jokes, I’m hereby copping to my complete enjoyment of their sentimentality — and, just as important, the way they use intertextuality (sorry for the awful academese; I mean the way books and movies make reference to other books and movies). This was prompted this weekend, when I went from watching “84, Charing Cross Road” (1987) to the magnificently crisp “Brief Encounter” (1945). Movies watching movies — I love the gimmick.

Confession: I started weeping almost as soon as I started watching “84, Charing Cross Road,” based on the Helene Hanff book. This one has all the elements: trans-Atlantic letters that slowly build a kind of romantic friendship between the funny, eccentric New York writer/reader (Anne Bancroft, whom I’ll watch in anything) and the withdrawn yet soulful London bookseller (Anthony Hopkins); discussions of the love of books and good writing; lots of shots of the interiors of bookstores and people reading. You just know that they might use awful words like intertextuality too, and then laugh at themselves. It’s like porn for those of us whose G-spot is located directly on our frontal lobe.

Midway through the film the Bancroft character goes to the movies and sees “Brief Encounter” (1945), the tale of two married, middle-aged people who fall deeply in love. Nothing could be more high-British than “Brief Encounter;” Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard have accents so posh and clipped they could make any good American democrat’s skin crawl. But it’s also got high romance along the lines of “Casablanca,” to which it has been compared. The film has so many scenes of them bidding goodbye to one another on train platforms, stealing furtive kisses on romantic bridges, and looking longingly into one another’s eyes (often on train platforms!) that one wonders how the otherwise impatient and no-nonsense Bancroft character could have kept her butt in the seat. Which, in fact, is exactly why the film has her watch this weeper classic: for all her love of the highbrow (John Donne, Walter Savage Landor, Samuel Pepys) and her meeting of the minds with the shy Hopkins, Bancroft shows us that she’s just as much a sook as I am by seeing it. Not just a sook, either: by indulging herself in this sweet British romance, Bancroft indicates a tinge of longing for a man far away whom she’ll never meet.

Don’t get the wrong impression: “Brief Encounter” isn’t merely sentimental pablum, and it seeks to establish this by having Johnson (as Laura) and Howard (as Alec) watch movies, too. Most memorably they see something called “Flames of Passion” of which we only see snippets — carnal desire played out in wildest Africa sums it up neatly. In this case, the clips of “Flames of Passion” provide a clarifying backdrop for the true love and high-minded restraint of Laura and Alec, who never consummate their love. And indeed, on its release the film was hailed for its realism. If this seems absurd to you, it’s only because you’re jaded by all those send-ups of “Brief Encounter” in films like “Airplane!” — or perhaps you’re the last to rediscover the poignant elegance of 1950s melodramas by Douglas Sirk. Set aside all your snark and watch this one from the beginning, paying close attention to the actors’ faces. Howard’s sharp angles and pocked cheeks make him a realistically ordinary man, most handsome when he’s delivering his yearning, lovesick lines. (This was his first starring role; I had only seen him before in “The Third Man” as the sardonic Major Calloway.) Meanwhile, Celia Johnson’s slightly pouty mouth, enormous eyes, and batting lashes combine elegantly, sweetly, with her unabashedly wrinkled brow to confirm she was getting close to 40 when the film was made. As such Alec and Laura truly appear to be everyday people, an ordinariness that makes their passion all the more bittersweet.

Don’t get the wrong impression: “Brief Encounter” isn’t merely sentimental pablum, and it seeks to establish this by having Johnson (as Laura) and Howard (as Alec) watch movies, too. Most memorably they see something called “Flames of Passion” of which we only see snippets — carnal desire played out in wildest Africa sums it up neatly. In this case, the clips of “Flames of Passion” provide a clarifying backdrop for the true love and high-minded restraint of Laura and Alec, who never consummate their love. And indeed, on its release the film was hailed for its realism. If this seems absurd to you, it’s only because you’re jaded by all those send-ups of “Brief Encounter” in films like “Airplane!” — or perhaps you’re the last to rediscover the poignant elegance of 1950s melodramas by Douglas Sirk. Set aside all your snark and watch this one from the beginning, paying close attention to the actors’ faces. Howard’s sharp angles and pocked cheeks make him a realistically ordinary man, most handsome when he’s delivering his yearning, lovesick lines. (This was his first starring role; I had only seen him before in “The Third Man” as the sardonic Major Calloway.) Meanwhile, Celia Johnson’s slightly pouty mouth, enormous eyes, and batting lashes combine elegantly, sweetly, with her unabashedly wrinkled brow to confirm she was getting close to 40 when the film was made. As such Alec and Laura truly appear to be everyday people, an ordinariness that makes their passion all the more bittersweet.

Women’s weepers are derided for being overwrought, but what really drives them is the seeming impossibility of romance in the real world, just like the narratives that drove so many 19th-century novels. Anne Bancroft lives a continent away from Anthony Hopkins, who’s married anyway. Alec and Laura aren’t exactly unhappy with their spouses, but their new love makes their respective marriages appear tedious. The director Douglas Sirk made this even more touching, with his treatment of the class and age divides between Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in “All That Heaven Allows” (1955). Just look at this clip from “Brief Encounter” in which Laura, in the full flush of new love, fantasizes about a life with Alec (“perhaps a little younger than we are now, but just as much in love”): this vignette shows us clearly what a ridiculous dream it is, yet it allows us to indulge, even as the pieces of newspaper fly through the ratty subway under the train platform as they kiss one another, and even after she gives up her ticket and walks home:

And oh, the dialogue! What could more beautifully indicate that delicious combination of passion and restraint:

Alec, intently: I love you. I love your wide eyes, the way you smile, your shyness, and the way you laugh at my jokes.

Laura, pleading: Please don’t.

Alec, more confidently now: I love you. I love you. You love me too. It’s no use pretending it hasn’t happened because it has.

Laura: Yes it has. I don’t want to pretend anything either to you or to anyone else. But from now on, I shall have to. That’s what’s wrong. Don’t you see? That’s what spoils everything. That’s why we must stop, here and now, talking like this. We’re neither of us free to love each other. There’s too much in the way. There’s still time, if we control ourselves and behave like sensible human beings. There’s still time.

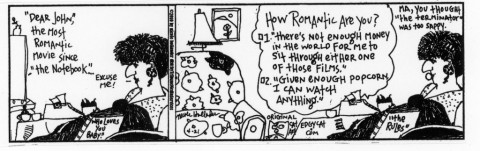

I’m telling you, go out and watch both of these movies — they’re brilliant, maudlin, beautiful things. We don’t need to secretly hate ourselves for enjoying this stuff; just use the word “intertextuality” and you’re inoculated. And besides, there’s always Sylvia to remind us that we can hate true pablum like “The Notebook.”